Reviews: Personal Shopper and American Honey at VIFF

/Still from Assayas' Personal Shopper

Personal Shopper (dir. Olivier Assayas)

In Olivier Assayas’ Personal Shopper, Maureen (Kristen Stewart) moves to Paris, the site of twin brother Lewis’ death due to a heart condition, with hopes of making otherworldly contact. Lewis was a medium, and though she also lives with this gift, it becomes clear that Maureen is fairly new at the practice. The house in which Lewis died, a grand, eerie mansion on the outskirts of Paris, has been put on the market by his partner and now sits empty. Maureen stays there alone, night after night, attempting to make contact with Lewis and communicating her findings to the prospective buyers (who have no intention of buying a haunted house). Doing this by dark, Maureen spends her days riding a moped around Paris, toting bags of couture—she’s a personal shopper for a high-profile model and designer—and has taken on the undesirable task of running errands for “nightmarish” Kyra (Nora von Waldstätten), in order to pay her rent. As Assayas previously demonstrated in his 2014 film, The Clouds of Sils Maria, the complicated power dynamics between women of varying success and position is an enticing mode of inquiry, and this film is certainly no exception. While we rarely see Kyra, her presence looms over the film, haunting it so to speak, manifesting in what seems to be Maureen’s pending nervous breakdown. While resenting Kyra fully, she indulges in the need to try on her clothes, drink her liquor and sleep in her bed. Indeed, what first seems a film about a personal shopper with an undesirable job and unconventional gift—a stylish, Parisian thriller—proves to be much more; a film less about ghosts and more about introspection, emotional vulnerability and the psychological process of grief and loss. Whether the plot and Maureen’s journey is mobilized by an internal or external presence is deliciously ambiguous, and Assayas skillfully refrains from giving the film a clear, overarching subject. Death and the afterlife are certainly prominent aspects of Personal Shopper; there is earnest integrity surrounding the discussions of historical mediums and incidents, and the framework of the film is one of supernatural faith. However, the force itself, whether it’s the afterlife, ghosts who know Morse code and have raging vendettas, or something more nuanced is posed to the viewer as an opportunity to assess their own beliefs. Ultimately Assayas’ lens attempts (and succeeds beautifully) to capture the deep complexities of loss—the intersection between belief, the after-life and coping.

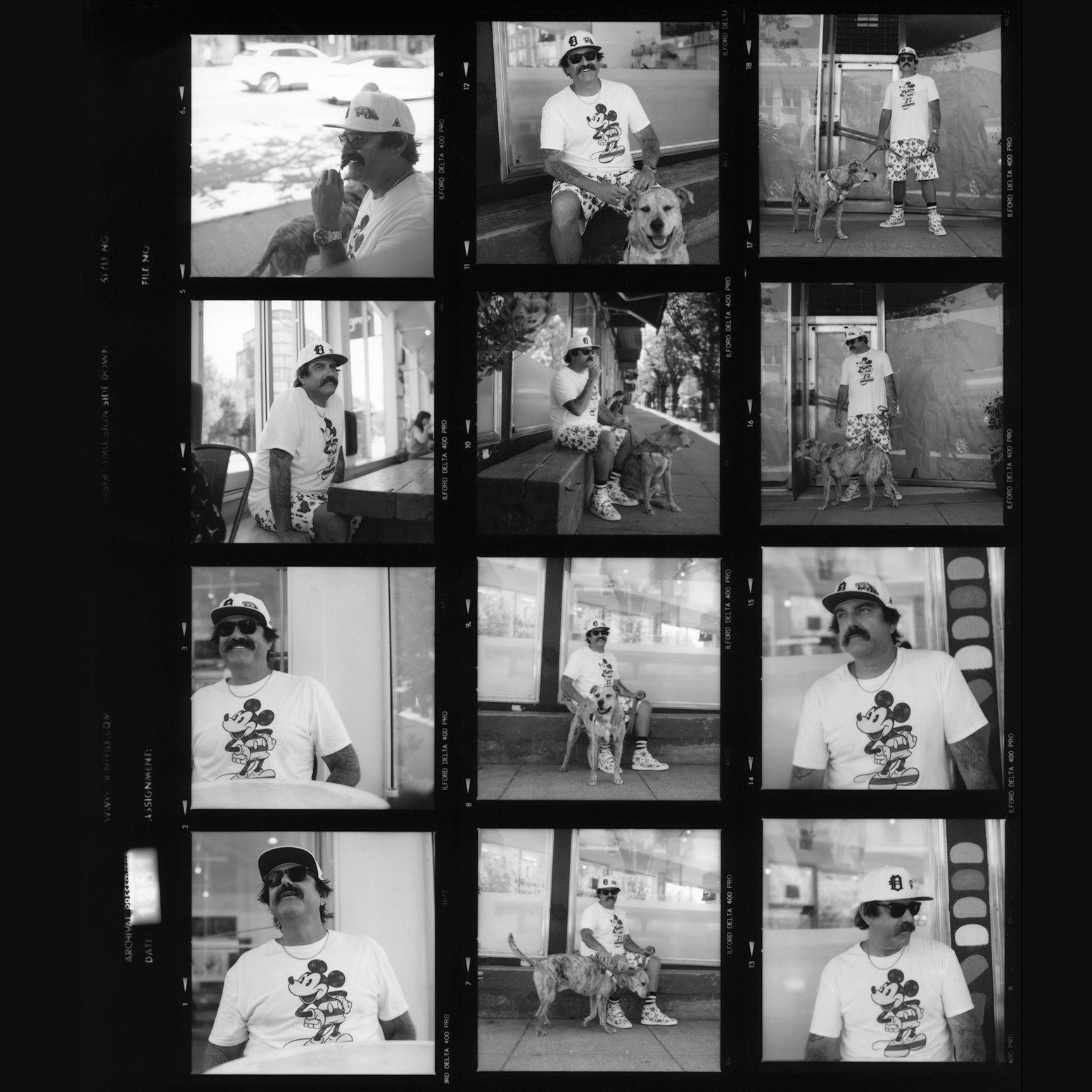

Still from Arnold's American Honey

American Honey (dir. Andrea Arnold)

Andrea Arnold’s American Honey is a meditative look at life on the fringes. Yet while Arnold’s previous films have garnered numerous awards, this feature, sitting at just under three hours, marks her most ambitious project to date. Star (Sasha Lane), a down-and-out eighteen year old, leaves her dumpster-diving life with her abusive step-father to join a van full of vagabonds making their way across the American Mid-West. Enchanted by the crew’s charming top dog Jake (Shia LaBeouf in his most impressive role yet) Star joins the ranks of the displaced, hard-partying youth, working for Crystal (Riley Keough) selling magazine subscriptions to fund their revelry, petrol and cheap motels. There’s a sustained lack of ambition within the crew, who are happy to work for little, subverting the sky-high sense of freedom and possibility associated with the American road trip genre—“everything ahead of me”, as Karouc once said—evoking instead a thoughtful commentary on the limitations of marginalization and scant prospect-hood in the land of opportunity. While this may seem cynical, especially from Arnold’s outsider British perspective, she brings her characteristic deep empathy and sensitivity to her subjects, making American Honey a pulsing portrayal of life on-the-whim, small beauty, recklessness and the infectious energy of being young and set loose on the world, as opposed to a cautionary or bleak representation. Arnold sought primarily inexperienced actors—newcomer Sasha Lane was spotted during spring break in Miami—and the authenticity of their dynamics and performances gives the movie a raw, intense realism. As the viewer, you feel like an unseen presence in the back of the van, sitting amongst them as they swill Smirnoff and sing along to Juicy J. Despite the intensely high energy of American Honey, it’s meditative at its core; a nuanced discussion of class discrepancies in the U.S., vulnerability and the cyclical patterns of poverty. However, this is mediated through optimism; the concept of “family” is explored, portrayed as something found, created and assembled—“home is the where the heart is”, the film seems to say. And there is a lot of heart. The footage of van sing-alongs are beautiful testaments to the pervasiveness of high energy in low places. Similarly, the bonfire scenes depict a tribal sense of rare community. American Honey tells of making your own freedom when there is little going for you, learning on your own accord, and discovering beauty in every moment. It is sweet, indeed.