Review: Lucy Raven's Tales of Love and Fear

/What happens when a site-specific installation goes on tour? Commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Centre (EMPAC) in Troy, New York, Lucy Raven’s Tales of Love and Fear is a site-specific installation built for the concert hall at EMPAC. It was presented at the Western Front in Vancouver for one night only, on Wednesday June 29.

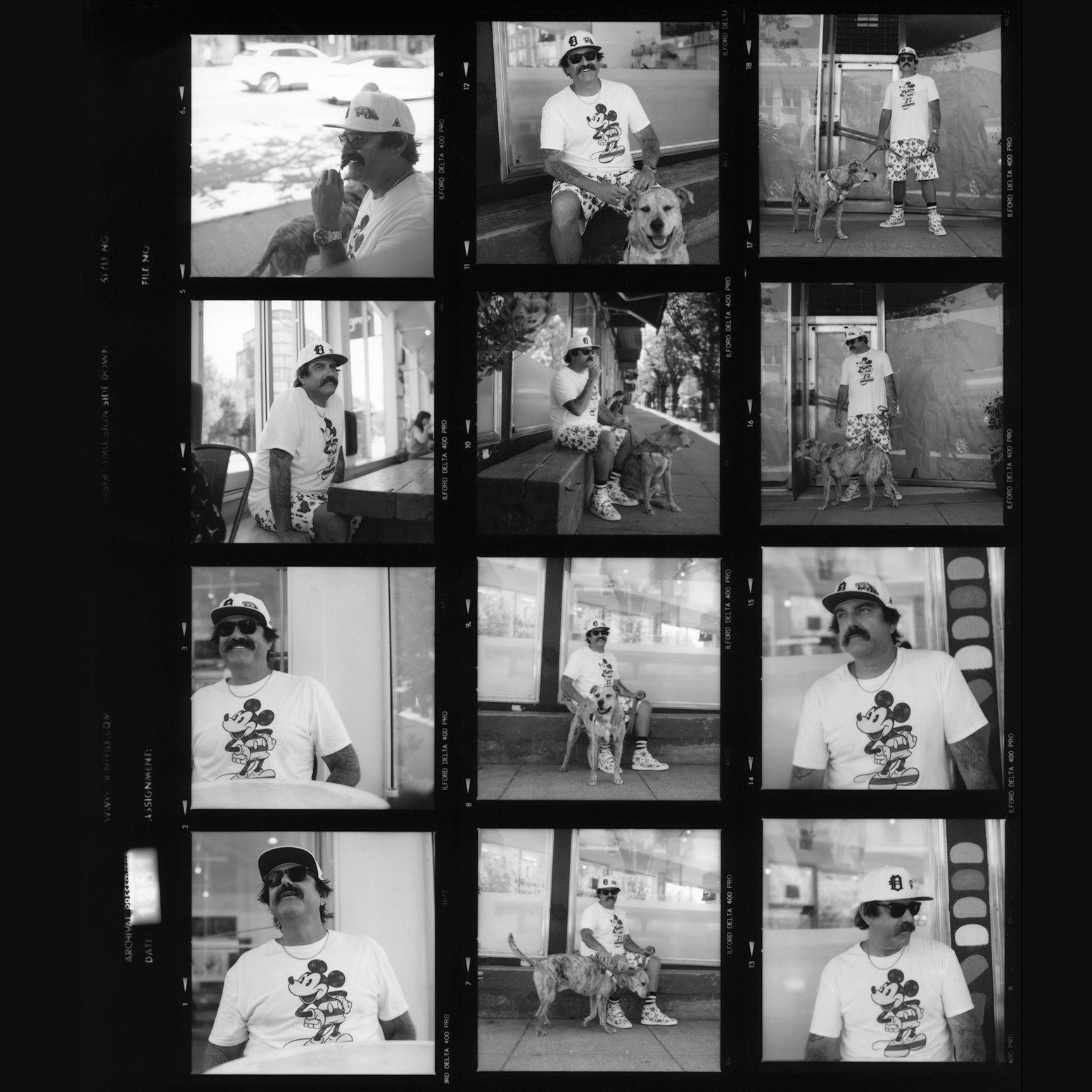

Poster for Lucy Raven's Tales of Love and Fear

Her installation consists of a custom-built rig of rotating platforms, a stereoscopic image split between two projectors, and sound based on field recordings made in India. Raven’s past work, including installations and her series of illustrated lectures, focuses on the formal relationship between low-relief carvings and 3-D images. She looks at different histories of low-relief carvings and the history of depicting spatial depth in India. In one of these lectures, she discusses Hollywood’s outsourcing to India of the work converting films to 3-D, a process that she calls both high-tech and artisanal. She traveled to postproduction studios in Mumbai, Chennai, and Trivandrum, as well as some of the oldest rock-cut temples in India, examining the ancient reliefs that exist in the same part of the world 3-D images are now produced. For Raven, the connection between ancient carvings in India and 3-D film-making in Hollywood is distilled in the single image projected in Tales of Love and Fear.

Of the many 3-D stills she took in India, the image she chose for the installation isn’t special. It doesn’t have a figure. It focuses on architecture—pillars, decals, and a sculpture. This is where the site-specific installation is compromised on tour: the image relates to the columns in the concert hall at EMPAC, an effect that was absent in the Western Front. Raven tells ArtForum she considers it to be “as much a movie as it is a kinetic sculpture performing the architecture of the theatre it is in.” The so-called performance of the image was lost on the dimension-less walls of the Western Front.

The most joyful moments of the installation were the first moments, when the theatre fell dark and everyone was facing the screen in silence. A glow came on from behind, though there wasn’t a projection on the screen ahead. The audience stirred as the field recordings from a theatre in Mumbai began to play and the screen remained blank. A few individuals began to turn around and see the image projecting on the back wall of the space. It was slowly diverging into two images—a red image moving to the right and a blue image moving to the left. Some people continued to face the screen longer than others, holding out against all the fidgeting in the quiet theatre. Eventually, everyone turned around, craning their necks or adjusting in their chairs to follow the red image or the blue image or alternate between both images as they slowly panned the walls of the room. Many people laughed—one person left—when they realized the creeping pace of the images moving towards the screen at the front to form the 3-D image.

In the installation, Raven slows down the process of looking. A big-budget 3-D film has thousands of frames while her film has one frame. The audience looks at the image for almost an hour as the 3-D image comes out on the screen at the front briefly, with the culmination of a horror film score—then the projectors continue to rotate again and the 3-D image is gone. Tales of Love and Fear unhinges production from time. If you can sit through her painstakingly slow installation, you will see the next 3-D film at your local mega-plex differently.

Though the experience is uncomfortable—purposefully, the opposite experience of getting lost to a 3-D blockbuster—it provides an opportunity to think about important issues that deserve much more than an hour of the audience's time. Tales of Love and Fear is an artist’s take on what the global economy has wrought, and challenges the audience to consider what actions are taking place to foil it.