Review: Executing Justice and The Man Who Sold the World at Fringe

/The 2017 Fringe Festival ran from September 7 to 17, and was full of exceptional theatre performance. If you missed it this year, be sure to start Fringe-ing next time around!

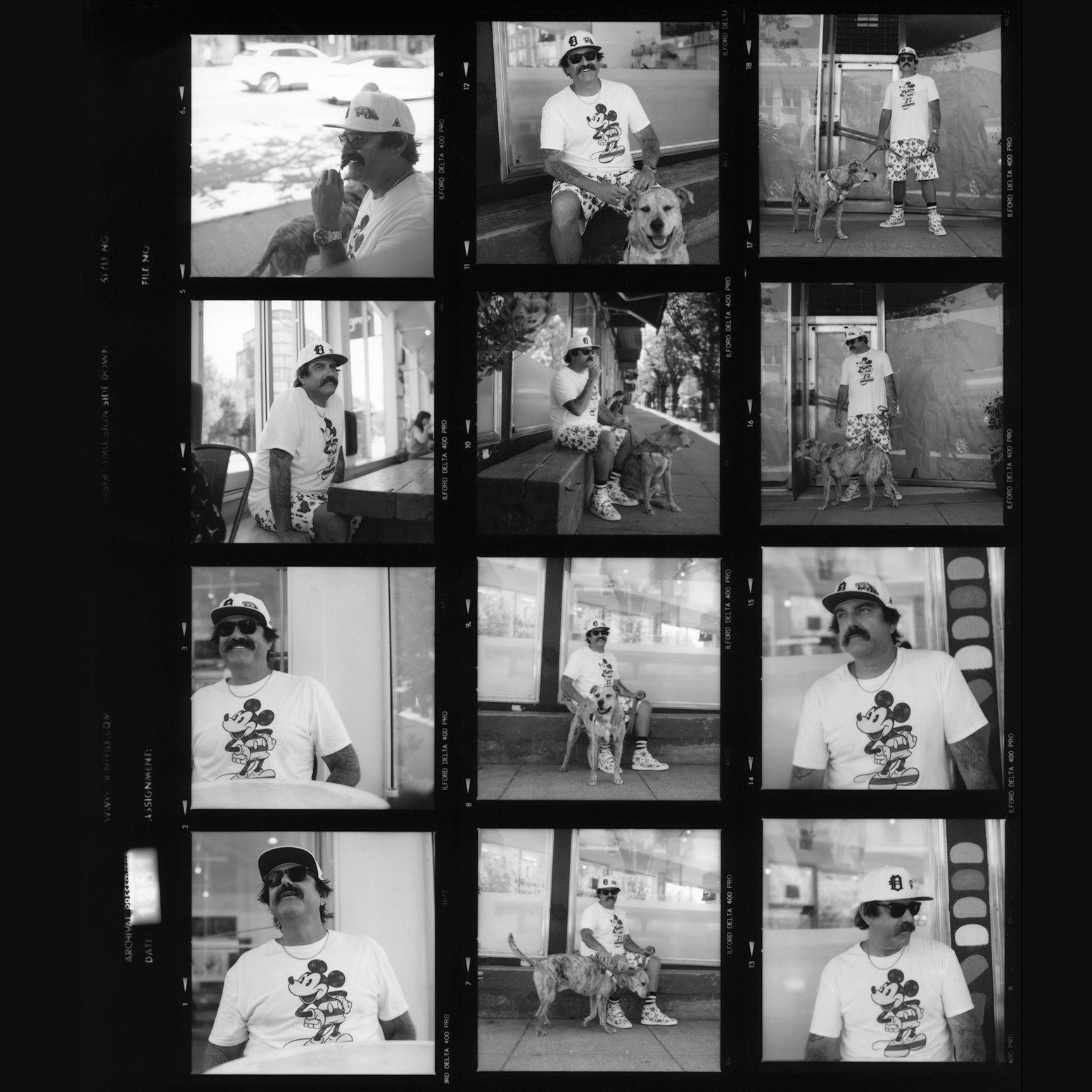

Photo courtesy of the Fringe Festival 2017

On the stage is a single wooden chair. In it, Bill Pats—the playwright and actor behind the one man show, Executing Justice.

The year is 2030 and Canada has reinstated the death penalty. Daryl Kane is the first person in Canada to get executed since 1962. The play follows Kane in his last hour.

The death penalty has always been a highly controversial debate, with a myriad of emotional, ethical, legal, financial reasons backing each side’s argument. What Pats does is personify these arguments by skillfully maneuvering between different characters to show the varying perspectives that are at the heart of the conversation.

There is an overworked psychiatrist who critiques the underfunding of helpful rehabilitative programs for individuals in the criminal justice system, as well as the cruel practice of solitary confinement. For the latter, he cites Kane as an example; Kane had already completed more than seven years of a drug-related sentence and had no behavioural problems in prison until the point where, in the midst of a prison riot, he stabbed another inmate and was put in solitary confinement. Upon his release, with few supports and deteriorating mental health, Kane snapped and killed a police officer. The psychiatrist berates a system that sets inmates like Kane up for failure.

There is the emotional older brother of the police officer Kane killed, who vehemently and furiously defends the death penalty for “animals” like his brother’s killer. And there is the equally emotional widow of the same police officer who speaks of the domestic violence that occurred behind closed doors, the unimaginable hopelessness and isolation of not being protected by the system that her abuser was a part of, and the overwhelming relief she had felt at his death.

There is a seasoned prison guard, brought in from Alabama to conduct training in the guard’s perspective of death row, being the person who spends the last hours with a man who knows his exact moment of death. The prison guard breaks down in tears as he speaks to the humanity of the inmates, and the crushing blows dealt upon those who work on death row.

And, of course, there is Kane himself. He speaks of his experiences of abuse in the foster care system, a system that often funnels its graduates into lives of poverty and crime, a system that does little to protect children and youth in its care. He talks of his life before prison, of how a one-time drug drop off led to death row through a series of unfortunate events and a deeply flawed system.

The play is short but it is haunting. As a society, we often place judgment upon individuals who have committed crimes and rarely upon the systems that drove them to that point. Everyone’s story is complex and behind each incarcerated individual, there is a system and a society that has failed them.

As Kane walks down the hallway to his death, that’s the message that lingers behind him.

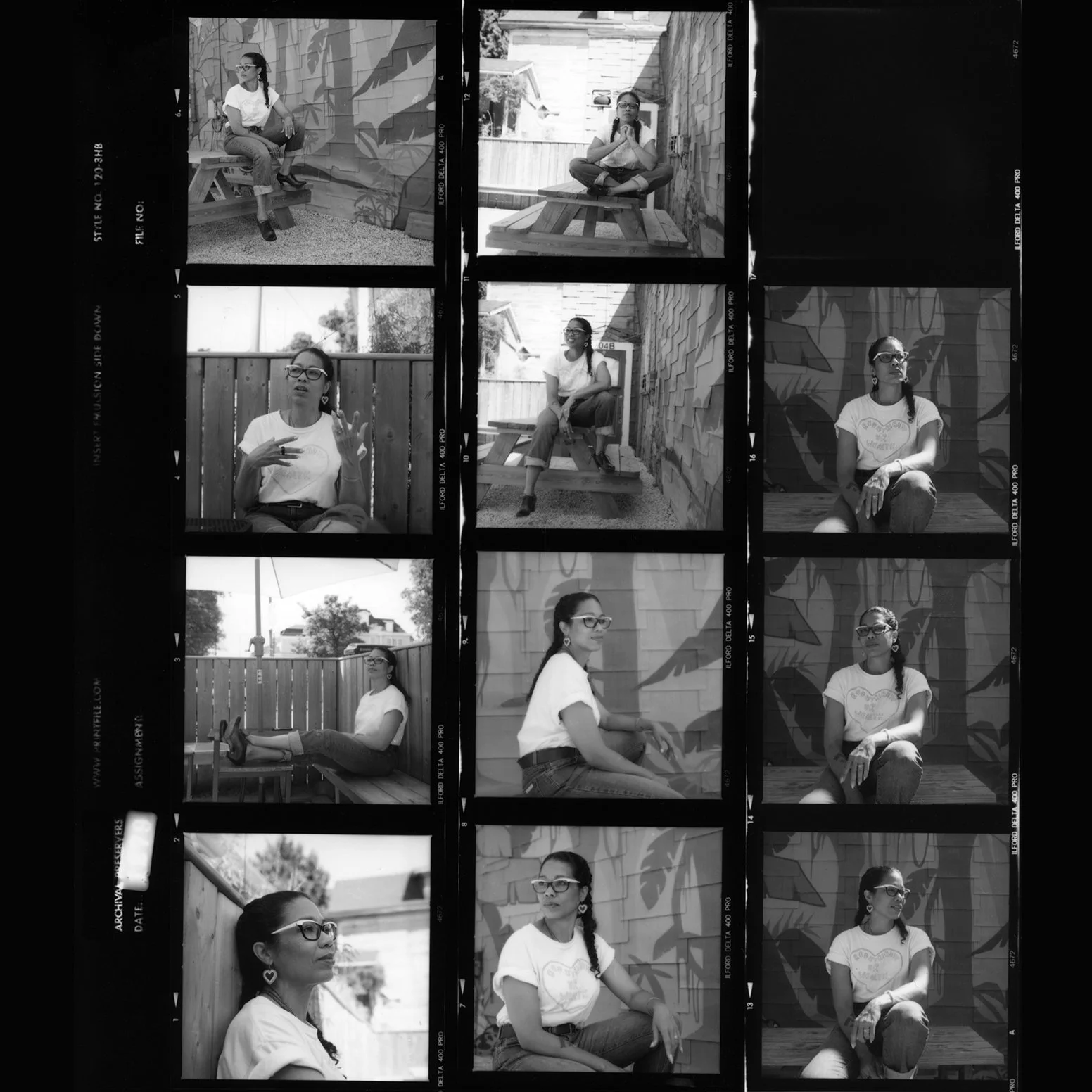

Photo courtesy of the Fringe Festival 2017

David Ortolando’s one man show, The Man Who Sold the World, takes place in a post-truth fictional land (one that holds an uncanny resemblance to current post-election America). Although originally written in the wake of 9/11 to address the collective fear triggered by that event, it is perhaps all the more relevant and poignant following recent political developments and the subsequent uncertainty hanging over us.

The show explores the hopelessness and darkness of our waning humanity in the face of socio-political chaos. There is a dream sequence, an alternate utopian world, and a main character who speaks in a jumbled combination of monologue, singing, and audience interaction; altogether, this made the play seem discordant and scattered. I was uncertain whether it was the artist’s intention to illustrate the feelings of confusion and unrest through performativity, or whether it was just inadvertently disorganized.

This is not to say that the subject matter came across as weak, or unimportant. Ortolando discusses how leaders, however corrupt they may be, come to power. He explains in depth how the political climate can have a crushing effect on our psyches, how we can lose ourselves and our moral compasses. He portrays the despair and helplessness that so many people feel in the face of what looks like a disintegrating society. He discusses our loss of humanity and connection to one another.

While none of these messages were lost on the audience, they were at times difficult to follow—a sort of messy stream of consciousness. The overall message was strong, the raw emotional energy was there, but what The Man Who Sold the World really needed was to meet its potential in a more cohesive presentation.