Review: Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster, Endings, and Pour at PuSh Festival

/The PuSh Festival ran from January 16 to February 4, and featured artists and performers galore. To visit the festival website and learn more about what went down, go here. Hope to see you at next year's fest!

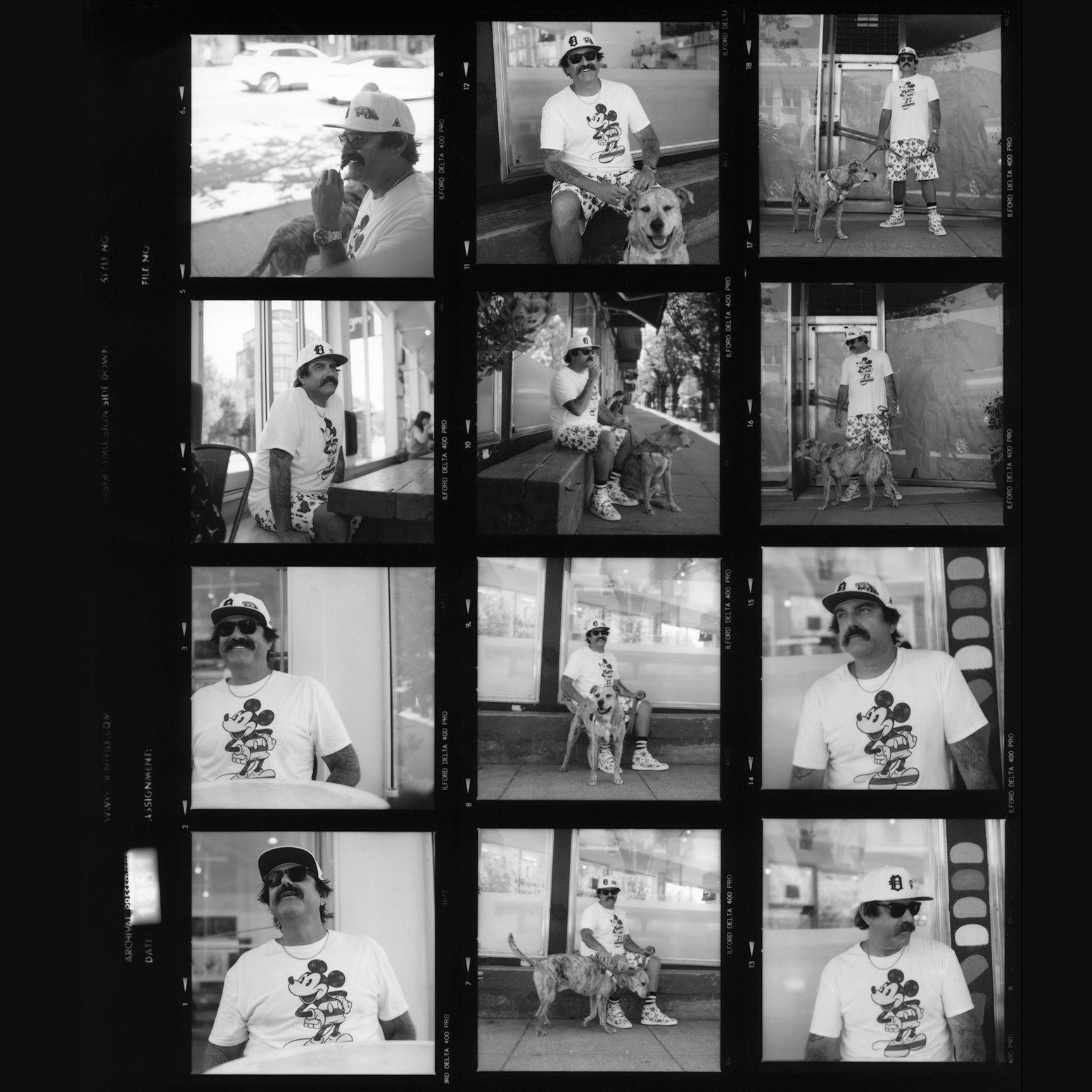

Photo by Sarah Walker

Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster directed by Nicola Gunn

“So imagine you’re a woman,” says Nicola Gunn, as she stands on one foot, her leg outstretched in front of her and in the palm of her right hand. “Imagine you’re a women in a foreign country.” She is now in a plank, still looking fiercely at the audience. “And this woman, in Belgium, sees a man throwing stones at a sitting duck.” She holds her plank for a second longer, her body barely shaking and her eyes steady.

Nicola Gunn is a Melbourne-based writer, director and dramaturg, who explores the fragility of the human condition through subversive humour and various forms of movement and performance. In her work at the 2018 PuSh Festival, Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster, one could expect to be provoked with existential thoughts on animal abuse, to laugh at obscure references to Marina Abramovic, and be consistently impressed by Gunn’s athletic ability and stamina. In this work, Gunn introduces to us a scenario—a scenario that she herself experienced whilst in Belgium—and explores the ethics of her own anecdote in a libidinally charged, comedically rich monologue, which feels like one side of a philosophical debate when out for coffee with a particularly fierce friend. Over the course of one rigorous hour, Gunn not only tells us the story of her confrontation with a man who was throwing rocks at a sitting duck, but explores the strangeness of human action and thought. And amidst the colourful text, a ghetto blaster on stage periodically introduces light, synth-y beats.

Photo by Gregory Lorenzutti

Gunn masters the pacing of the monologue not only through her conviction of language, but through her use of unexpected body movement. Whether or not the piece is choreographed, it feels hyper-impulsive, each movement stressing the points in her fierce and rambling argument. To make sense of this piece is like asking the reason for a five-year-old’s meltdown. However, what is significant is how Gunn explores the restricted setting she has provided for herself. It is as if she is asking us: what would any human do if left for an hour with a ghetto blaster? And in answering that question, we experience something so specific to her own human experience and condition; what the performance has to say about the complex irrationality of human reaction, argument, and existence. As we ponder all of this, Gunn closes the show, her back to the stage, wearing a technicolour dream-coat as laser beams dart across the room in time with a final, pounding synth beat.

Photo by Sarah Walker

Endings directed by Tamara Saulwick

There are four turntables across the stage. A few large lamps hang low above them, swinging gently, illuminating the turntables as well as outlining the various bodies across the space. Tamara Saulwick moves towards one of the turntables and places needle on vinyl. A recording of a women’s voice quietly echoes through the space. We do not know the woman to whom the recorded voice belongs to. She says, “I said to her before she died: I’ve brought a mattress, I’ve brought blankets, you never have to be alone again.”

In her piece Endings, Tamara Saulwick explores the unsettling beauty in death and loss by orchestrating a soft yet striking audio-visual experience on the stage. The stage is simplistic and vast in it’s darkness, instigating a loss of place, much like that associated with the dark, unknown arena of death. The performances feature many sensory elements occurring simultaneously, the majority of audio deriving from pre-recorded interviews pressed onto vinyl records, with unknown individuals speaking about their own experiences with mortality and loss. Endings is a meticulously orchestrated experience, during which the performers carefully organize and play the various recorded voices, combined with live audio of spoken text (some of which mimics that of the recordings) as well as live music from Australian singing group Grand Salvo.

Photo by Prudence Upton

As the piece unfolds before the audience, we are confronted with the realities of loss and morality. Voices speak about watching the life leave their loved ones, followed by Paddy Mann’s soft acoustic voice singing, “and if your face is in the soil/and in your eyes the threads of roots and creatures coil/a hole just like a broken bone, flowers grow.” The show is so gentle in it’s touch, the recorded voices hushed and the acoustic music delicate and intimate, and yet the gravity of the subject matter leaves one feeling heavy. At one point, Tamara Saulwick sits on a stool and begins to converse with a recording, which you realize is a psychic reading from a medium. The medium asks Tamara about her father, and Tamara twiddles her thumbs. She answers: “Well, he wasn’t a chatterer but, he liked to talk, he liked to really talk and ask people questions.”

In this ominous, painfully beautiful work, Saulwick manages to address one of human life’s greatest fears and anxieties. Whether you have lost someone in your life or not, the piece speaks to the fragility of humanity, and the complicated, unknown space of death and it’s abstract nature. Saulwick utilizes the stage to create a timeless, placeless location, where ghostly narratives weave together as they discuss the un-discussable: the intangibility of loss and mortality.

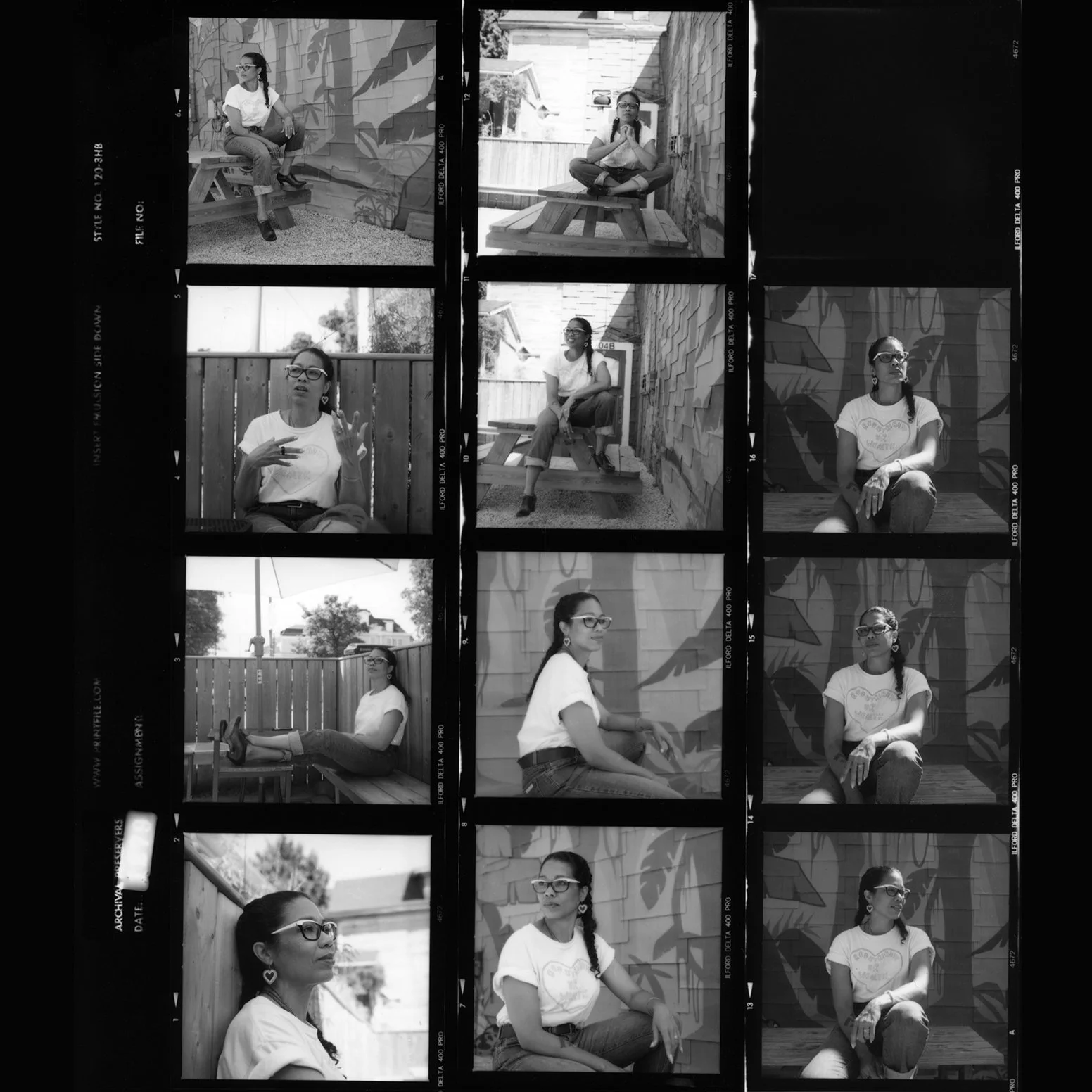

Photo by Daina Ashbee and Alejandro Jimenez

Pour directed by Daina Ashbee

When I told my roommate I was going to see the solo movement performance of a nude female, he immediately made a comment about the Number Five Orange. Mostly annoyed, yet somewhat interested in his comment, I kept it with me as I found my seat for the performance of Canadian performer and choreographer Daina Ashbee’s piece, Pour. I quickly realized that my roommate’s comment strongly relates to the many topics that this piece addresses, one being the immediate sexualization of the nude female body on display. Presently, as well as throughout history, the female body is a subject of objectifying gaze, a thing meant for consumption and projection by a predominantly, yet not restrictedly, male-identifying audience. In her provocative work, Daina Ashbee explores the notion of assumed objectification of the female body, and what baggage the female nude carries.

As audience members are finding their seats, the stage is dimly lit, and one can only somewhat make out the outline of a pacing figure. The figure periodically sings a sustained high pitched note as she paces. This continues as the audience files in. The lights ever so slowly dim until the room is pitch black. Suddenly, the room is fluorescent bright, the light so strong in comparison to the previous darkness that it hurts my eyes. At the front of the stage stands dancer Paige Culley, topless and wearing a pair of jeans. She stares at the audience, who aren’t in the comfortable shadows of darkness but are just as lit with light as Culley is. She has an unforgiving stare, one that makes you feel seen, addressed, and confronted. Culley slowly peels off her pants, keeping her gaze on her audience as you watch her undress. This female nude isn’t letting you just watch her; through her confronting stare, she has identified you as a witness for what is to come.

In addition to the themes of femininity and the presumed object that the female body has become, one of Ashbee’s main explorations in this piece is the cycle of menstruation embodied through movement and performance. The pace of the piece begins at a painfully slow rate. Culley lowers herself to the ground and moves in a circular motion around the stage, utilizing her head and her feet as her main points of contact with the floor. Her core is often arched or flexed; there is great attention paid to her midriff and it’s concave curve. Through these movements, there is also great attention paid to the labour of the body as it moves. Uncomfortable angles and unexpected positions reminded me of what the body can endure, specifically the various discomforts that the female body experiences throughout menstruation.

Photo by Daina Ashbee and Alejandro Jimenez

As the piece becomes more violent, the audience is interrogated with ideas of bodily harm and assault. The smacking sound of Culley’s limbs against the styrofoam stage is the only soundtrack that fills the space, along with her labouring breath. The smacking continues, and as her body shakes at the impact, you almost want to look away, to plug your ears, to turn away from the violence. Ashbee’s choreography is purposefully mesmerizing in it’s beauty, only to confront you with extremely uncomfortable violence in the following moment. Again, I am brought back to the female body, and the violence that it endures: the violence of menstruation, the violence of child birth, the violence of the undying male gaze and objectification, the violence of assault.

This is followed by terror, as Culley lets out a series of blood-curdling screams, their repetition unforgiving. She paces the stage aggressively as she lets out her cries, and I was fearful as to what would happen next, as if this was the warning of some great approaching horror. Perhaps the terror I felt was because these were screams that we all know too well; the screams of female pain and suffering that sometimes we aren’t able to hear. In Pour, Culley embodies a female process that isn’t always accredited for it’s fortitude. In this harsh, yet meditative performance, Ashbee's choreography confronts the audience's role as witness by presenting us with an unforgiving, haunting, and visceral presentation of the female body’s endurance.