reach-close: an interdisciplinary exploration of instruments and identities

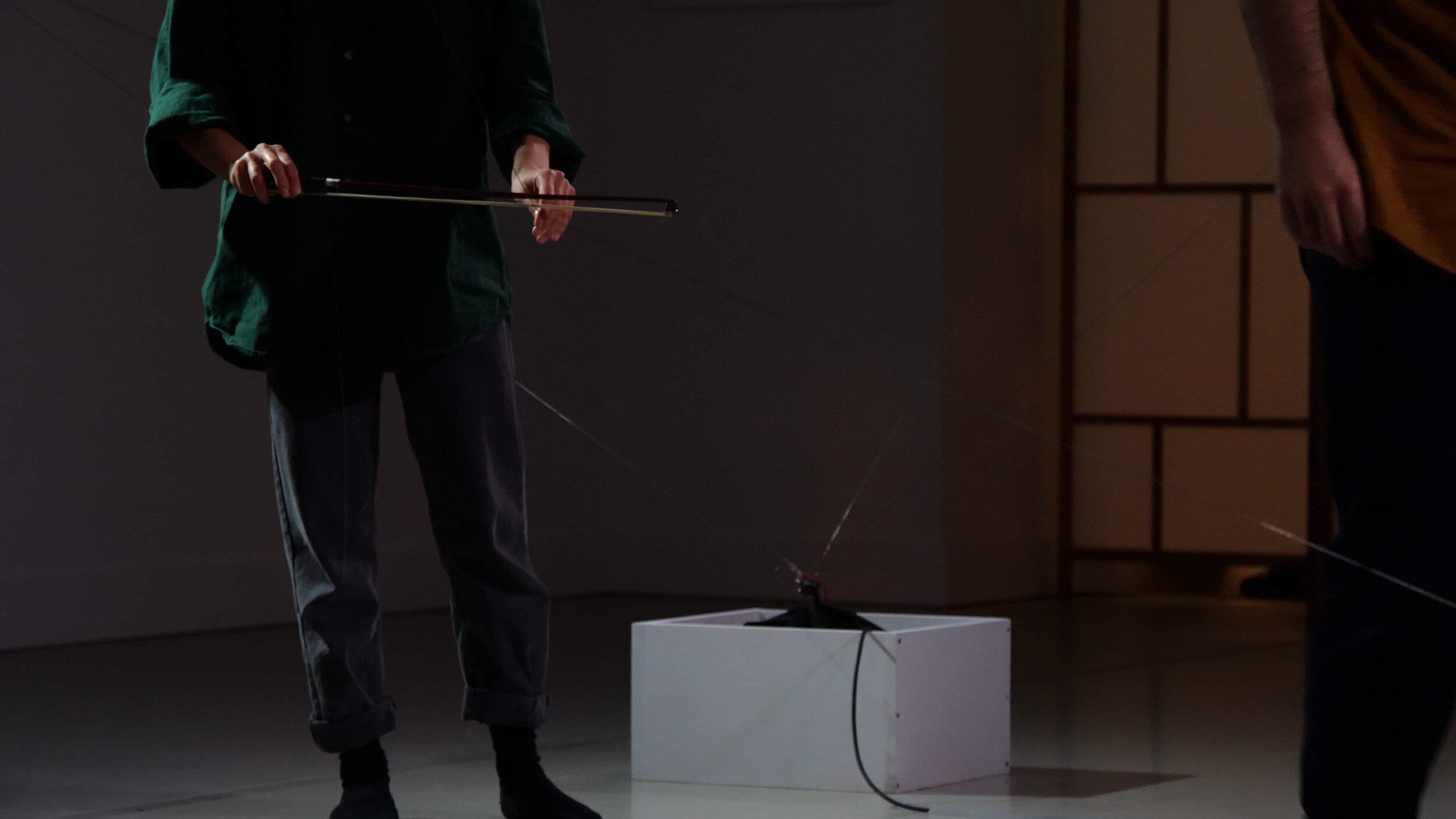

/Picture a dimly lit room, furnished solely with piano wires stretched floor-to-ceiling in angular arrangements. When the house lights rise, two performers with matching buzz cuts move towards a piece of wire. They roll their heads along different cables, never breaking contact as they slowly twist their bodies. A sound echoes, like a string being bowed or softly plucked. Several pitches combine to create a texture, sounding almost like a sandpaper violin. The lights go down, and when they return, the performers now have a bow in hand and begin playing the stage wires like an instrument.

Musician Stefan Nazarevich and dance artist Shion Skye Carter are part of the collective olive theory, and co-produced the show ‘reach-close’ —an Interdisciplinary work that deconstructs the rules defining what an instrument should look like, and how it should be played.

Nazarevich has been playing music since the age of five, when he asked his parents for piano lessons. He trained classically on the piano for 18 years, and later developed a taste for electronic music. Eventually, he found himself in Simon Fraser University’s music program.

“There is a certain amount of gatekeeping within the institution,” says Nazarevich, who found that the program favoured certain methods of playing and composition. “I find that when you make music more intuitively, with less of an emphasis on it sounding ‘pretty’ or ‘right,’ music making can be a more curious, and accessible process, which is exciting to me”.

Carter has been dancing since she was 12 years old, an age she says is a late start compared to others. Her entry into the world was untraditional as well—through her high school’s modern and contemporary dance program. After graduation, she was accepted into SFU’s dance program.

“It was an interesting experience, coming from a background of dance that was quite different from everyone else,” says Carter. “Immediately, there was a comparison of my body’s dance ability with the others there.” Rather than feeling restricted by her differences, Carter attributes her background as what helped her move more intuitively, within the programs emphasis on improvisational composition.

While Nazarevich says he “can’t dance for shit,” and Carter’s piano knowledge is limited to one song, the pair saw an expectation-free opportunity to combine disciplines to create their own artistic language.“We don’t have to accept that I’m more of a dancer or more of musician” says Carter. “Your chosen discipline isn’t the only way you can create. If anything, more discovery comes when you step outside of what is known and comfortable.”

When the duo began work on the project in August 2018, they knew that they wanted to create a concept that could have various iterations. The first ‘reach close’ debuted during plastic orchid factory's 2019 season, with two sold out shows. Recently, the duo premiered a research-in-process version at Left of PuSh, which examines the relationship between the embodied and the semi organic with the synthesized and purely electrical.

“We wanted the instrument to structurally be its own entity, and take up the space with us—as if it were also a performer,” says Nazarevich. “The way you define this thing is the way you relate to it”.

Nazarevich assumes a more pedestrian relation to the instrument, while Carter places a dance gaze on the instrument. Both artists beg the questions: How do these relations look gestural? Does movement create a compelling sound? The answers took form through this performance piece.

“We experimented a lot with how we could touch and interact with the wire, whether it was plucking, tapping, bowing, or rubbing our buzz cuts up against it,” says Carter, adding that it took three months for the instrument to even make a sound. In the end, the most successful method was tethering three contact microphones to the bottom of each cluster of piano wire. Each contact mic has three different sound effect chains, which can be changed and controlled in real time through a panel.

“We wanted there to be a unique closeness to the instrument,” says Carter. “ And for the sounds that we were making to be dependent on the parts of our bodies we were using to play or how we moved.”

What I enjoyed most about this work, was how it challenges the self-serious art body. While a knowledge of music and art theory will always aid deeper discussions surrounding the piece, ‘reach-close’ manages to be accessible to a variety of audiences. Even the performers themselves are working outside of their known comforts, being a musician when they are a dancer, or dancing when they are a musician. This sense of play and modest artistic exploration establishes a welcoming viewing environment.

Next Carter and Nazarevich are looking to explore how to make the work more accessible, public and interactive. Maybe just the motion of someone walking by causes the instrument to make a sound, creating a moment of potential confusion, curiosity and pause within a stranger’s day. Either way, the pair has created a very interesting and fluid framework to explore both instruments and bodies, and how they can combine to create music in different ways.