Documentary Short Review: Joe Buffalo

/Joe Buffalo is a 16-minute documentary short with feature impact. It’s one Cree man’s story of surviving Canada’s genocidal residential school system and breaking cycles of intergenerational trauma to become a skateboarding icon.

Directed by Vancouver-based Amar Chebib and executive produced by professional skater Tony Hawk, the award-winning film was distributed for free by the New Yorker on October 6th.

“Skateboarding was like a savior, given the circumstances of me growing up,” says Buffalo in his opening narration. The line is both the dark cloud and bright light that hangs over his story.

A member of the Samson Cree Nation born in Alberta, Buffalo was taken from his family and forced into the residential school system at eleven years old. The schools were notorious for their deadly cultural assimilation practices and the sexual and physical abuse of children.

Buffalo describes falling asleep in crowded dorm rooms with children who, like him, had only seen their parents a few times per year—falling asleep to the cries of his classmates and the sounds of “spirits in the walls from the dark history there.”

He was the last generation to attend, following the painful path of his grandparents, parents, and siblings.

When Buffalo left the school in his early teens, he picked up a hobby that would become his outlet—skateboarding.

Archival and dramatized footage shows a smiling tough guy landing edgy, gravity-defying street tricks, relentless in his determination to go pro.

But when his big break came, Buffalo describes how he let it slip away like sand between his fingers. Low self-esteem characterized that era of his life, he says, as he repressed deep-rooted childhood pain through drug and alcohol addictions.

With a soul-piercing gaze to the camera, his dimly lit face conveys visceral anger and sorrow—a mark of the film’s minimalist direction, driven by the honest potency of emotional narration.

“Deep down, I was miserable,” he says. “I made some mistakes over those years that caught up with me. Jail damaged my spirit and I felt like a caged animal.”

But Buffalo never lost his fire. Instead, he found the courage to reignite and redirect it.

Three overdoses after his release, he became sober and faced his suffering head-on, doggedly committed to interrupting the harmful mark that the residential school system left on his family.

“Sobering up made me stronger. I took all that energy that I would put into partying and survival and put it back into my skateboarding,” Buffalo says.

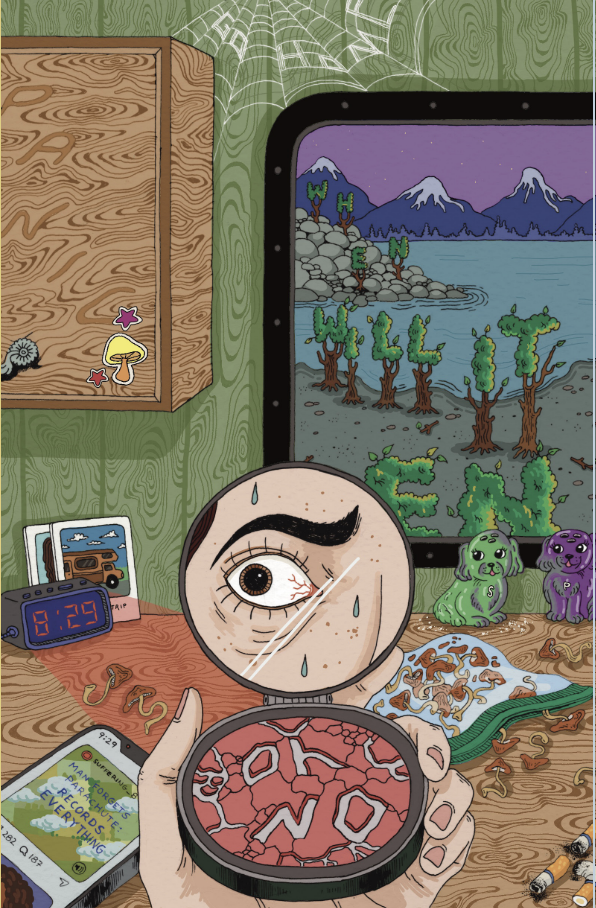

And it paid off. Defying industry norms, Buffalo became a professional skateboarder at forty-one. He proudly designed his first professional skateboard model after Chief Poundmaker—a revered First Nations peacemaker and Buffalo’s great grandfather.

The film proves that Buffalo’s story is one of hope. It’s a hope felt in the body, beating to the soundtrack of powerful Indigenous vocals—the true pulse of the film, thanks to sound designers Matt Drake and Kaitlyn Redcrow.

It’s a contagious and heroic hope as Buffalo, a Vancouver resident, glides along familiar downtown streets, riding rails at the infamous skate park under the Georgia Viaduct.

It’s a powerful optimism that he now channels into education—inspiring kids to believe in themselves through skateboarding.

And it’s a hope that carries to the film’s closing line—a line that envelops the heart of Buffalo’s story: “If I can make it happen given the circumstances of how I was raised then there’s hope out there, man.”

Follow Joe Buffalo on Instagram and watch the documentary short here.