In Conversation with Greg Durrell

/As Canada approaches its sesquicentennial, it’s hard to believe that Greg Durrell’s upcoming film Design Canada is the first project to document the history of Canadian design.

Greg, a Gen X from ’83, tells me over the phone that this project began almost twenty years ago, back when he was in high school. An avid collector of records, he was struck one day when he realized it was someone’s job to design the cover art.

“I started noticing that I was surrounded by so much beauty in Canada that I couldn’t find any information about,” Greg recalls.

At the time, he was attending St. Mikes, an all boys high-school in Toronto that has produced some of Canada’s best hockey players. By tenth grade, he was on the rink less and on the computer more. The world was experiencing the “dot com” boom and the rise of the internet was not only exciting—it was changing the face of art. He transferred schools and enrolled in a specialized “cyber art” program where half the day was spent studying traditional art, the other on video, desktop publishing and the like.

As he recalls some of the first designs that excited him—Canadian National Railway’s single thick line, the train tracks and movement that happens in one pen stroke; the Montreal Olympic’s logo, a perfect hybrid of sport and design—his voice becomes louder and faster. The mere act of describing his favourite designs brings Greg right back to his sixteen year old self.

That’s how old he was when he got his first job in design, and he’s never had a job of any other nature since. The job was with a design firm in Toronto creating HTML flash (“all the rage back then!”) for Stella Artois.

“Getting a job at this time was easy if you could type on a keyboard and knew a bit of coding.”

His career trajectory sounds like a fairytale in today’s day and age, where even those who can type, code and have their Master’s degree are working as baristas. Greg on the other hand, never completed university, having dropped out of the Ontario College of Art and Design to pursue his dream of being on the design team for the Olympic Games. That dream came true, and today it’s hard to imagine a Canadian graphic designer who’s work has been seen globally more than his in recent memory.

“I’m always working,” Greg explains of his reputation and success. “If I’m not working on client projects, I’m working on personal projects.”

Design is in him, it’s who he is, but he’s the first to admit that a work/life balance has been difficult to reach. His company, Hulse & Durrell, is a presenting partner of Design Canada, which Greg has dedicated all of his weekends and vacations to working on. His associate, Ben Hulse has been extremely supportive of the documentary, carrying the company torch for Greg when he’s on the road for research.

“He wants answers to these questions too!”

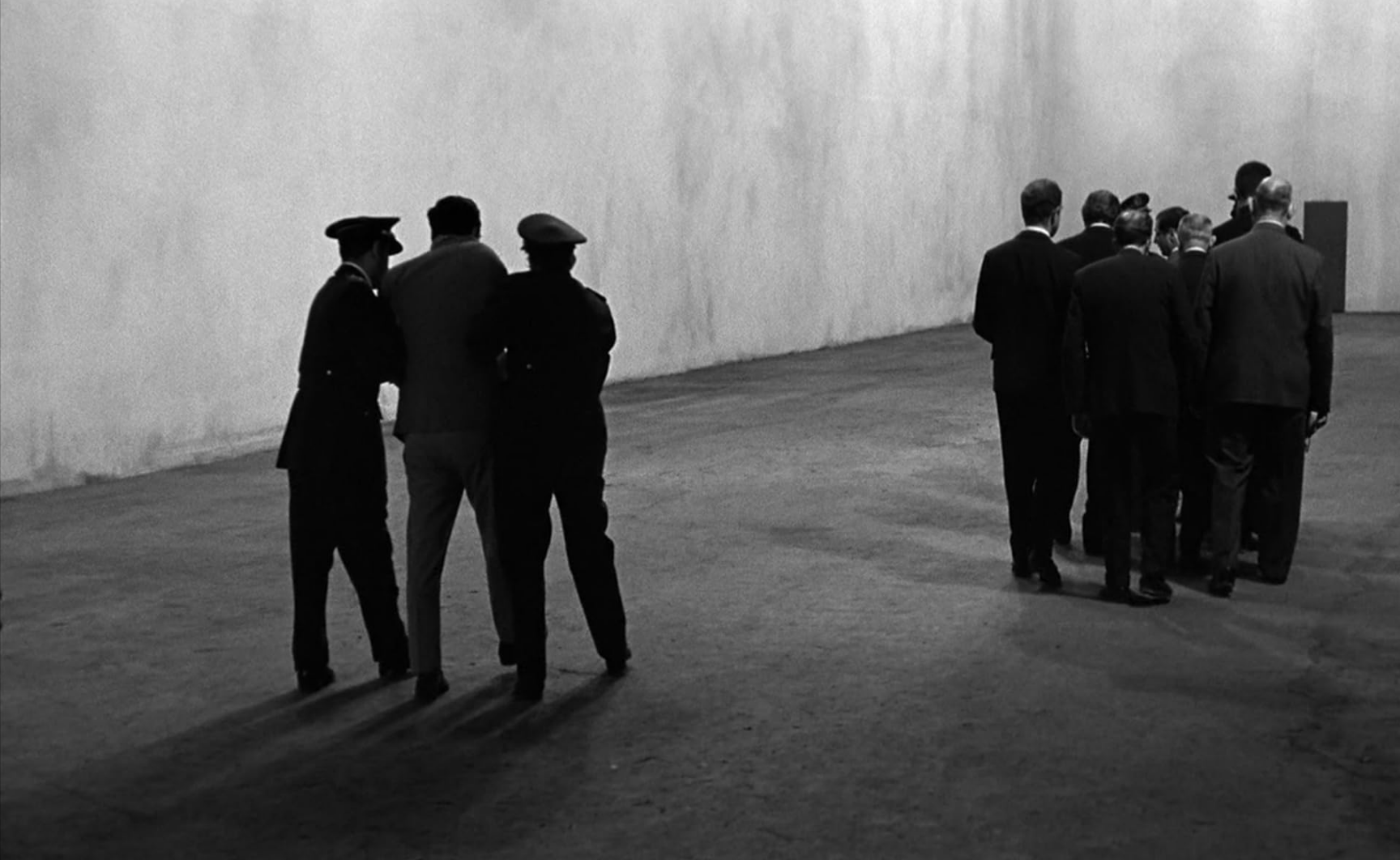

Poster for Design Canada

Even for a passionate workaholic like Greg, the challenges of making this documentary were overwhelming at times. He started from a blank slate and had never made a film before. Greg taught himself how to operate the camera equipment through Youtube tutorials and was unclear as to whether he’d end up doing anything with the documentary. All he knew was that he had to capture the story of Canada’s design pioneers, many of whom are in their eighties.

“Instead of going to film school, making this documentary was my film school,” Greg says, laughing as he adds, “the whole thing was really fucking hard. Making a documentary feels like you’re aimlessly wandering through the dark.”

Though it’s hard to find your way, Greg insists that if you keep at it you’ll figure things out. It also didn’t hurt to have Jessica Edwards and Gary Hustwit on as collaborators. Greg had a mutual friend who connected him with Jessica, an esteemed documentarian who was eager to help Greg with this ambitious project. Gary Hustwit’s film Helvetica is what Greg claims opened his eyes to the power of film.

“It made me realize that you can make a movie on a niche topic while making it accessible to the public. Generally, only designers would think about these things, but it effects everyone everyday. Think of how difficult airports would be to navigate if the signs were designed poorly.”

He’s wondered “who are the design pioneers in Canada?” And “how has their work impacted the image of Canada?” Since he was a teenager. Besides a few magazines that never went into depth, he could never find anything documented about the golden era of design for Canada.

Fritz Gottschalk (left) and Greg Durrell (right)

In the 60’s, Canada was looking to makeover it’s image. After the contributions Canada made during World War 2, it no longer made make sense for the country to keep a hand-me-down flag with a union jack. We became our own entity, far more unique than a mere colony.

Art in the ’40’s and ’50’s was very illustrative, involving lots of penmanship and a palpable human presence. Through the rise of the Modernist movement in the ’60’s, design was being approached objectively—suddenly, authorship was being stripped from art and designers sought to communicate without personal style. Beautifully reduced geometric forms suddenly became abundant.

“Really, the use of the maple leaf goes back centuries,” Greg explains.“Indigenous people used maple trees and sap as part of their harvest for food and materials. Canadian athletes were represented by the leaf even before it was on our flag.”

Human’s have always had a tendency to resist change, so it’s not surprising that some resisted 1965’s new flag design. People thought there should be a beaver on the flag or something that included Britain and France. However, because design was innocent enough and Canada was in the right place at the right time, George Stanley’s design was approved and lives on today.

“Fifty plus years later, a lot of people never question the flag,” Greg says. “It just feels right and that’s what great design is—it has a timeless quality.”

Canada, Greg believes, is one of the most well branded nations in the world. Just look at the consistency in every letter from the government, or the Canadian embassies around the world with an identical look and feel. Because of our French and English culture, the government was aware early on that any brand system created needed to treat each culture equally.

While the documentary is about Canadian design, Greg travelled all around the world to find answer to his questions. He interviewed design pioneers living in Canada’s remote towns, big cities and abroad in places like Fort Lauderdale and Switzerland.

“These were the same people whose work inspired me to be where I am today, so I definitely had moments of being a bit star struck,” Greg admits, emphasizing how appreciative he is of all the designers who participated in this project. “So much time was donated to this project. A lot of times I literally cold called these people out of a phone book.”

Burton Kramer (left) and Greg Durrell (right)

Greg hopes the film will give Canadian designers the credit their work deserves, all while allowing Canadians to realize the amazing design in their own backyard. While there are other incredible designers around the globe, Canada’s golden era of design shouldn’t go undocumented or uncelebrated. We have a a young prime minister who’s putting a lot of time and energy into the image of Canada and a big birthday coming up. With so much divide going on in the modern world, our country has returned to a point where it needs to re-examine it’s image.

“I hope Design Canada makes Canadians walk with a newfound swagger,” Greg jokes.

A beautiful and relevant aspect of the film is how it highlights the important role immigration played in creating Canada’s identity. Our country had a very forward thinking immigration policy in the ‘50s and ‘60s which allowed multi-cultured designers the ability to live and work in Canada while contributing to its international image.

When I ask Greg what makes Canadian design truly unique, he immediately groans, saying he hates this question and is constantly asked it.

“Design is something that’s international: it’s problem solving, and exists to communicate a message in the best way possible. Because of that it’s international, Canada doesn’t do anything specific.”

What makes Canadian design worthy of its own film, Greg explains, is the fact that it was perfectly timed. The rising of design and our redesign as a country worked in tandem to touch the nation.

While all of Greg’s projects have a piece of his heart, this film will be the project he’s most proud of when it’s unveiled. Design Canada has been pitched to several big festivals, and the documentary is set to be released this fall.

The Design Canada team is currently fundraising and they need your help! If you'd like to support the creation of this awesome project, visit their Kickstarter page for more info and instructions on how to donate.