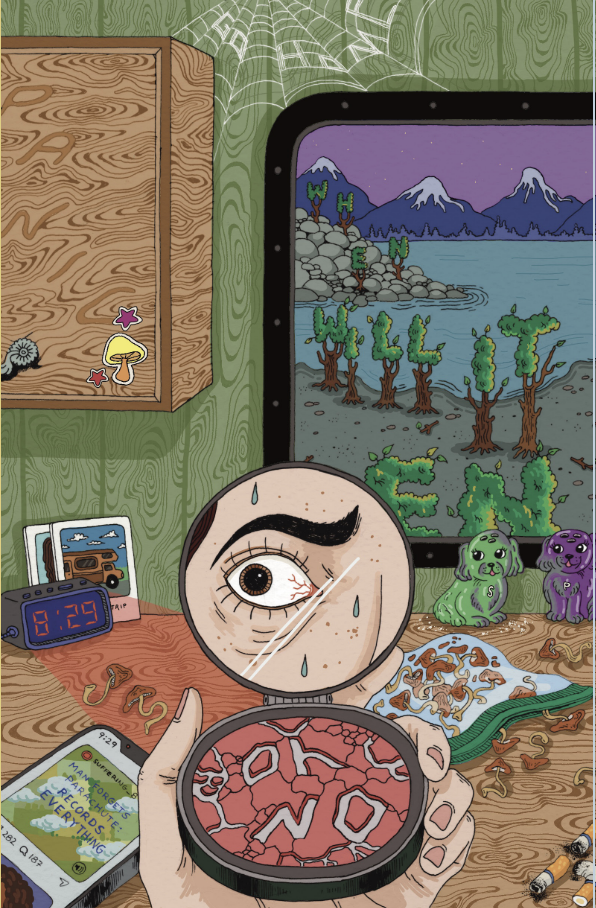

Review: The Condor and the Eagle inspires interculttral climate action

/An Indigneous-led climate awakening campaign has kicked off a national tour with a Vancouver screening of The Condor and the Eagle, a documentary by Sophie and Clement Guerra.

“When the eagle of the North and the condor of the South fly together, Indigenous peoples will unite the human family.”

This is the prophecy that inspired and opens the film, which follows four Indigenous leader’s journey from North America to the Amazon rainforest. The northern segment of the documentary focuses on energy hotspots in Alberta and Houston, which host tar sands, pipelines and contaminated lands. As fossil fuel developments get out of control, entire Indigenous populations are displaced in favour of industry, while the oil leaching into their fields and water sources goes ignored. The audience witnesses countless protests, town halls, concerts and gatherings organized by activists and community members, as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike do all they can to show political leaders how the human and environmental costs of pipeline projects are not worth the economic boom.

A tribal councilwoman, Casey Camp-Horinek of the Ponca Tribe in Oklahoma, highlights the genocidal implications of these industry projects.

“The manner in which they are killing us now isn’t smallpox, it’s environmental destruction,” says Camp-Horinek, noting that it’s not just Indigenous communities who will feel the impact. “We all live downstream.”

The consequences are especially personal for on protagonist, Melina Laboucan-Massimo of the Loubicon Cree First Nation in Alberta. Following her sister’s recent death, Laboucan-Massimo is connecting the violence against Indigenous women and girls to the violence against Mother Earth. She believes women are meant to protect the earth, therefore violence against one party begets violence against the other.

Meanwhile, Texan Bryan Parras is an environmental organizer who has only recently connected with his Indigenous roots. While learning the dances, songs and language that his people use to connect with the land, he is also fighting the destruction of that land.

These are stories from the eagle—the North. The journey South highlights the overlap between these stories and those of the condor.

On the other hemisphere, the film introduces more people who are displaced for industry, told that they will receive support and new homes. Instead, they find themselves in poor living conditions without the freedom to access their traditional lands. We learn about companies who lay topsoil on an oil spill and call it clean; governments who change the thresholds for environmental permits so that industry is never held accountable.

According to new data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has surged to its highest rate in more than a decade. Meanwhile, Canadian energy companies are actively planning to triple our nations tar sands through planned pipelines throughout Canada and the U.S.

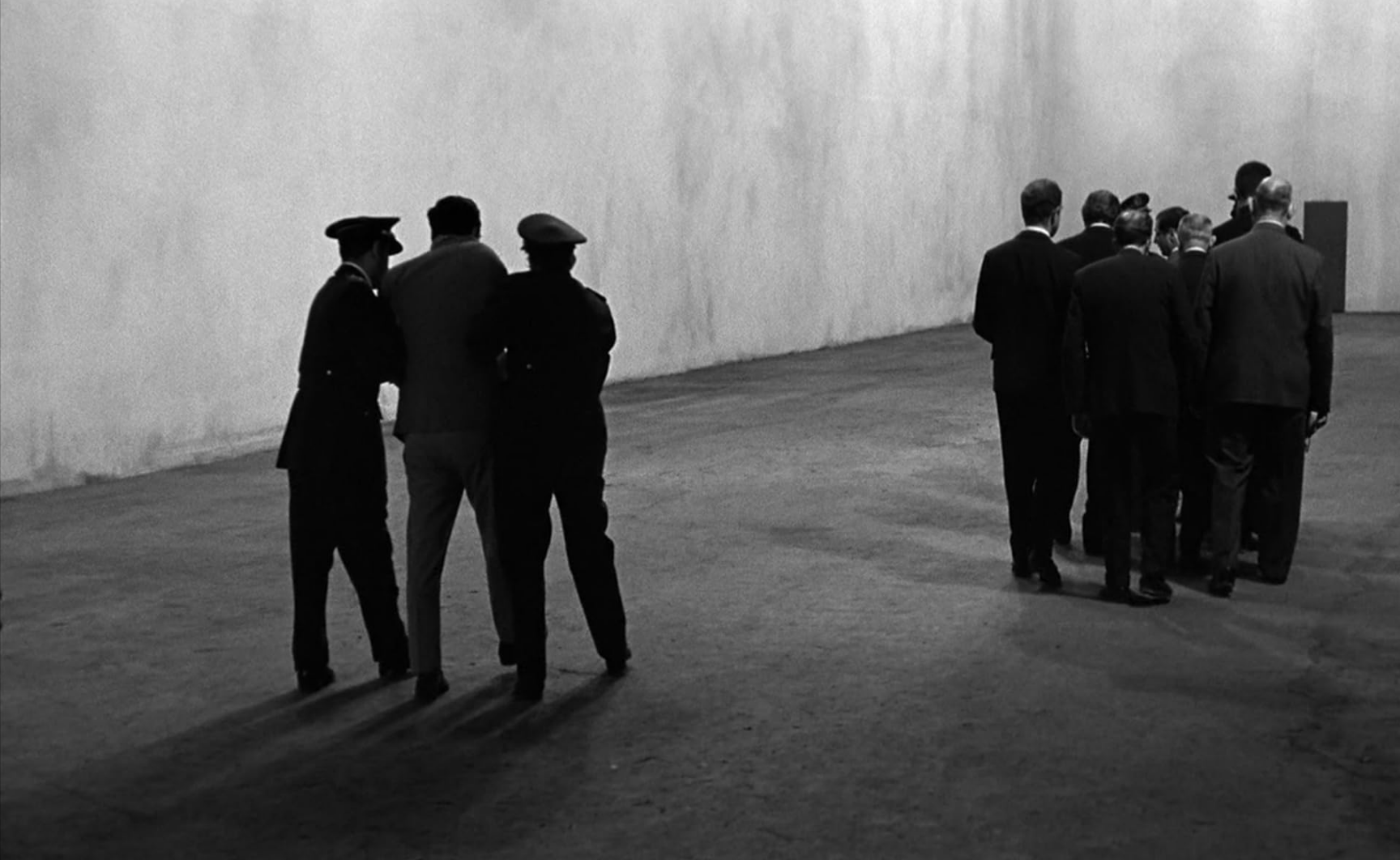

Watching this documentary, I must confess that my first sense was one of hopelessness. The protests in the film mirror those for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Standing Rock and others in the North—they are impassioned, angry, defiant and determined. Yet the brick wall of government, policy and industry remains unmoved.

However, when the group is travelling through the Amazonian rainforest, they encounter the concept of a “minga.” A minga, their guide explains, is what happens when a community works together to reach a common goal, one that benefits everyone and cannot be accomplished without their cooperation.

Now that they are connected, they are a part of this minga. The condor and the eagle may begin to fly together.

Through this incredible transcontinental journey, the film hopes to spotlight the ways in which Indigenous women are leading calls for a sustainable future, all while pushing for the enforcement of their rights. By amplifying these voices, the documentary looks to educate communities who may lack Indigenous knowledge in order to mobilize urgent, collaborative and intercultural actions.