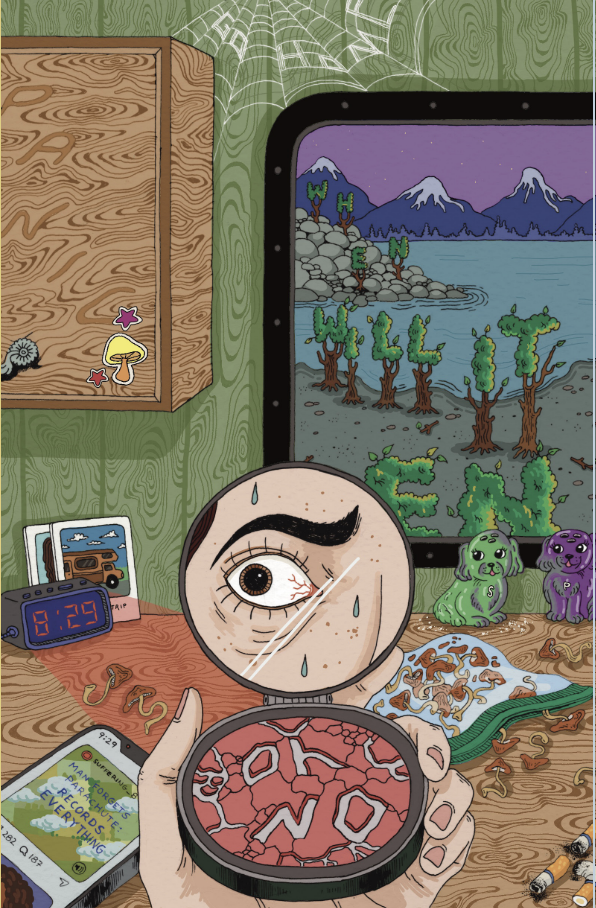

Meet December's Featured Artist: Michael Love

/Architectural Study #3 from the series Shadow Architecture, 24x26”, Inkjet Print, 2018.

Michael Love is a photo-based artist living in Vancouver. His career spans decades and continents, where he has documented and explored the repurposing of spaces in relation to history. He is particularly interested in military history and the impacts of the Cold War. Much of his work has documented what remains and what has formed in sites of conflict, from Albania, to the Diefenbunker, to Canadian military bases abroad. He uses a research-based approach to explore for himself the significance of the technologies and ideologies of this time period, then uses his research to propose new and more nuanced ideas about history, time, and space through images and aesthetics.

Statues from the series Enver Never, 20x25”, Inkjet Print, 2014.

SAD Mag: Please introduce yourself.

Michael Love: I’m a photo-based artist. I studied at Emily Carr and Concordia, and I’ve been doing photography for about two decades or more now. I’m interested in sites of conflict, how we negotiate living with those spaces after the conflict’s over, and how we come to inhabit the space, reuse the space, and renegotiate the space. I’m interested in the idea of intergenerational trauma and the legacy, especially of the Cold War, as a specific time period where we got to the point where our technology could eliminate [us] or make us extinct.

Tattoo Parlour, from the series Enver Never, 40x50”, Inkjet Print, 2014.

SAD: How would you end up inhabiting that space? Were there experiences in your life that connected you to this work?

ML: Where my interests started was where I grew up, in Chilliwack. When I was a kid, the second-biggest employer there was the military base. My family was there because my grandfather served in the military. My grandfather was in the military for at least twenty years, and he served overseas in Germany twice; NATO had military bases there during the Cold War. My mother, in turn, Grew up in Germany.

It was an interesting environment to grow up in. My grandparents all worked on the military base, so I spent a lot of time there as a kid. In retrospect, there was a lot that was unusual about growing up there during that time because I think there was a lot of paranoia around the Cold War with people in the community. For example, I had a high school social studies teacher who kept a bag packed and hiking boots in his cupboard in case there was a bomb coming.

In the late 90s, they closed the base there and decommissioned it. The homes on it were turned into low-income housing for awhile, but it was close to a wealthier neighbourhood, and they started complaining about social problems. They sold all the houses to a development company for a dollar a piece, who did a renovation project and made them look like modern homes; they sold them for about $400,000, which was unattainable to the people who were evicted. I documented the renovation process.

From that, I became interested; there were a lot of politics in the way the base was decommissioned. When that was happening it was at the same time we were starting to send troops to Afghanistan: cutting spending in one area and moving it to another, changing the way the military worked as a peacekeeping and defensive military, and into something more offensive. It was an interesting time.

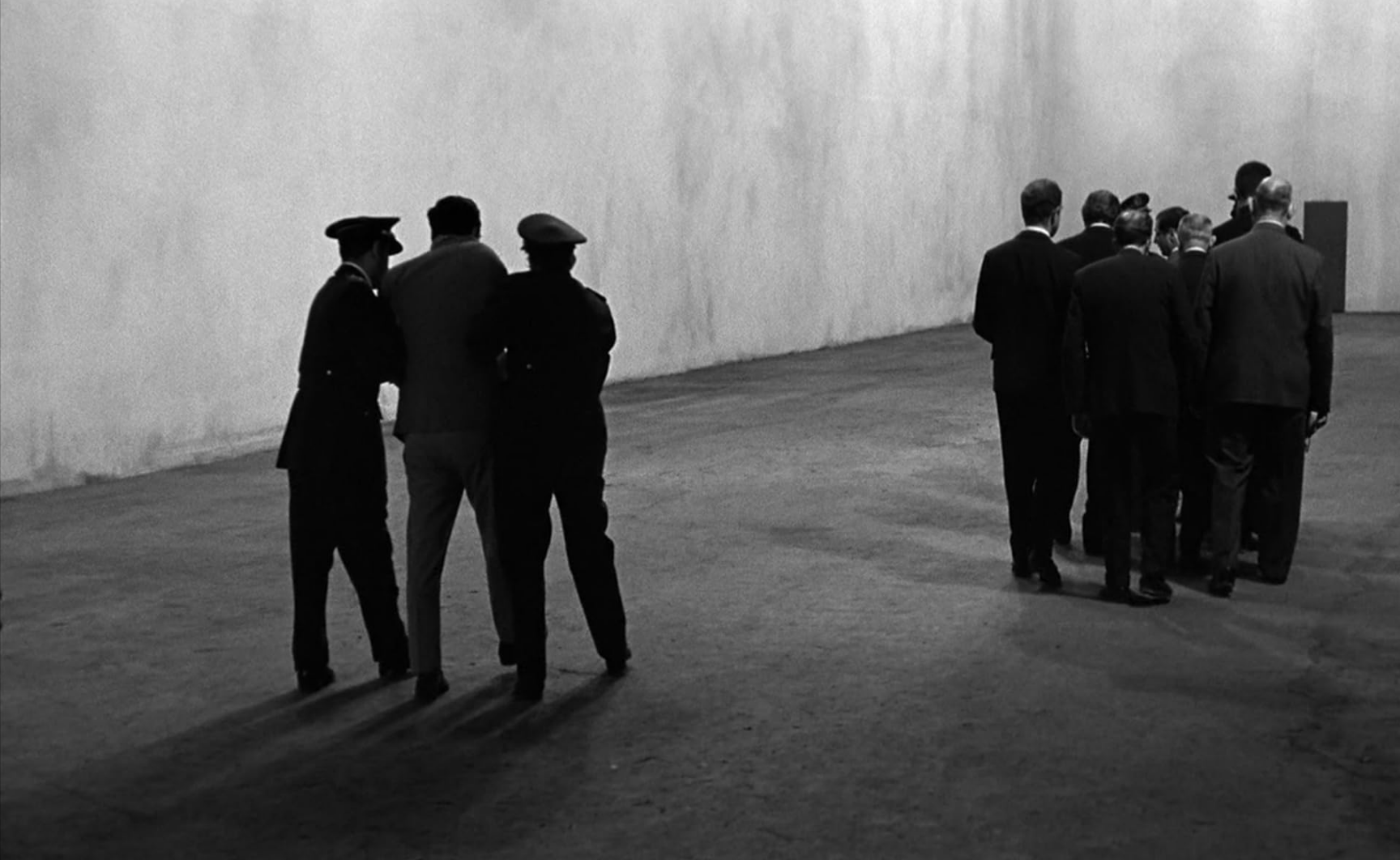

Theatre: Fort St. Louis from the series: The Long Wait, 40x50”, Inkjet Print, 2009.

SAD: What is your view of the military now?

ML: I’ve never been a pro-military type of person. In the past I’ve seen it as a necessary evil. Under the Harper government, the ideology of militarization became popular, for example, the highway being renamed the “Highway of Heroes”. I find this type of strong patriotism very concerning. I was interested in the Cold War when I started, because I didn’t think it was over; and I’ve found that it really isn’t over.

Architectural Study #9 from the series Shadow Architecture, 24x26”, Inkjet Print, 2018.

SAD: What lens are you applying then, when it comes to what you document or how you document?

ML: It’s multi-faceted. It’s the history aspect, and the ideology that there’s two systems that work in opposition to each other. I’m interested in the idea that there’s this propaganda on either side about how the other system is wrong; the thing that happens is that it’s really just average people who are thrust into the existence of living in these systems, and that people are the same almost anywhere you go.

I’m also interested in remembering these events, because if we forget these things they're bound to happen again. It’s not that all these bad things came out of it. There’s a lot that came out of the military research that happened that enhance our lives everyday. We wouldn’t have a cellphone without the military. It’s interesting how that even got wrapped up in ideology as well.

SAD: How did you arrive at repurposing or re-imagining history and images?

ML: I’m interested in manipulating history or reconfiguring it as opposed to just a more documentary tradition. I did a project in Germany where I went to all the Canadian military bases that were abandoned, and became aware of how those spaces were being reinterpreted. A lot of them turned into industrial areas where there’s manufacturing; one of them they were using as a refugee camp; one they were doing training on.

That became more prominent in my work—looking at how people were repurposing these spaces became really interesting to me, because what are the implications of living in a military site and turning it into your home? I was interested in how I could interpret the sites for myself, and that’s how I started working with historical images, cutting them up. recomposing and making my own propositions for the spaces.

SAD: What are those propositions?

ML: It’s more of an aesthetic exercise more than anything. I did a residency at the CBC with the Vancouver Heritage Foundation and was asked to make a work. They really were looking at engaging with Vancouver’s built environment against the backdrop of Reconciliation. The CBC doesn’t have a lot of photo archives. They were looking for a two-dimensional work, so I went to the City’s archive. There’s nothing really that old in Vancouver. I was looking at an archive of images of the city, it became very disorienting, because you could never place any space, even if you knew where it was. I decided to engage this covering up and rebuilding side of this fantastical structure, and out of that, I became interested in this conflating time and space within the work.

In the Shadow Architecture project that I did, I was looking at American military sites as they emerged as a superpower. Mostly in the continental US, there was an ideology that was being transmitted through those spaces. I was trying to bring various locations together: chemical-producing sites, mining sites, places that contributed to their ability to become a superpower and the technological development.

Architectural Study #8, From the series Shadow Architecture, 24x26”, Inkjet Print, 2018.

SAD: How do you decide where to go?

ML: I work intuitively, and most of my work is research-heavy; the research comes before the work comes. The way I work is by looking at historical events, paying attention to the news, and what’s going on. Once in awhile something comes up that piques my interest. I stew over something for a couple of years before I pursue it.

Space Museum, From the series Artek, 40x50”, Inkjet Print, 2010.

SAD: Do you mean you take time to form the idea? What does that look like?

ML: It’s a matter of raising money, applying for grants, and sometimes it takes time for ideas to materialize. For example, when I went to Ukraine to photograph Artek, I heard about it on the radio. Artek was a children's camp set up by Lenin in 1925 and it’s still operating in Crimea. They don’t let people into that campground. I applied for a grant at the same time I heard about it, and got a grant to go.

I had some contacts who knew people in Ukraine, so I was emailing with them. I contacted the Ukraine embassy here, and the Canadian embassy there, until someone told me nothing would happen from Canada.

I got flights and rented a place to live in three weeks in Yalta. I booked the apartment through a guy in the UK. He basically said, “a woman Ljudmila will meet you, if you need anything, she speaks English.” She asked me what I was doing in Yalta, and when I said “I’m trying to go to Artek,” she said, “oh, my daughter-in-law works there.” It was Ljudmila who did a bunch of phone calling and found someone who would give me a tour.

Bleachers, From the series Artek, 40x50”, Inkjet Print, 2010.

SAD: What are some upcoming plans for your art?

ML: Currently, I’m interested in going to Austria and Germany to study Brutalist architecture. I think that’s an interesting architectural form that has an embedded ideology that’s sort of utopian. There’s this socialist stance that everything should be the same, everything should function, and have no hierarchy in the architectural form.

I’m also interested in applying to the War Artist Program. The Canadian military has a residency where you can be an artist-in-residence and be embedded in the military. I’m proposing to go to Ukraine. Canada is training Ukrainian soldiers how to fight against the Russian invasion. I feel like that’s the front line of the new Cold War, and it could be interesting to do a body of work on that.