Reifying nostalgia with tender confrontations

/Rydel Cerezo is a photographer that works towards reifying a space between sexuality and religion, race and beauty, and identity and culture. He holds a BFA from Emily Carr University, where we met during our first year of schooling. He meets me at a familial space—my home in East Vancouver. We chat about his practice as well as two of his most recent photo series.

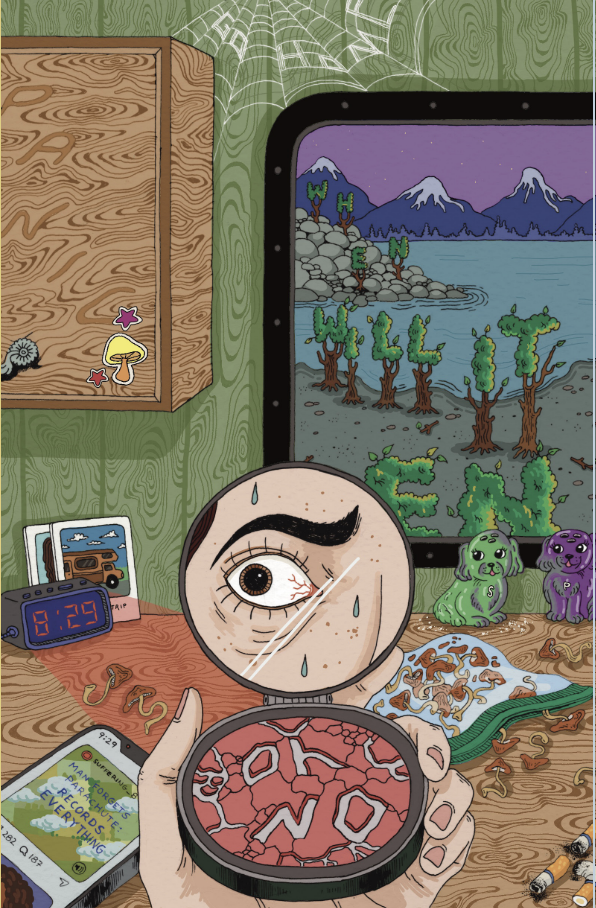

Familial spaces is one of the themes in the series titled Am I a Sea (2019). This series, which he completed during his last year of undergrad, is a veritable portrait of the complex reminisces of his Catholic upbringing as a young, queer, Filipino immigrant. Am I a Sea is now scheduled to show at the Delirious Cities exhibition from July 25 to August 29, 2019 at the Aperture Foundation Gallery in New York.

From Am I A Sea, 2019

Angie Rico: One of the first encounters I had with your work was during our very first semester in Henry Tsang’s photo class, one of the assignments was to create a series around the theme of “self-portrait” and I remember you took a beautiful photograph of your mom’s belly with her pregnancy stretch marks. I’ve noticed that you photograph your family a lot. Your family, now in the form of your little brother Kai and your lola (Tagalog for grandma), are at the center of Am I a Sea—can you tell me why?

Rydel Cerezo: I can’t believe you remember that. For Kai, he was my very first model when I started photography. In this project I would see him and be thinking about myself in a very selfish way. Especially for this series I was using him to be me, using his physicality to represent me being younger. I have always had a very close relationship with my lola and I wanted to not only visualize my own relationship to the church, but complicate it more. It’s not only the things I learned directly through the church, but it’s also how my familial context informs my learnings of the church. My lola represents this added layer.

From Am I A Sea, 2019.

In speaking about the transference or inheritance of trauma, the figure of lola represents that memory, while Kai represents this aspect of ongoing knowledge. The two forces feel very palpable in the series. The subject matter is represented as documentary in some ways, but at the same time Cerezo is constructing this memory; there is a play between something that is staged and something that is a documentary.

These stylistic translations are very present throughout his body of work, though his practice extends greatly into diverse platforms such as PhotoVogue Italia, Leen Magazine, Vanity Teen, among many others where his fashion work has been published.

Photo by Rydel Cerezo

AR: How do you navigate work that is personal and work that is related to fashion?

RC: It’s quite difficult as an artist and photographer when you feel like you have to split these bodies of work. I always feel very torn because I value both of them. Process-wise it is quite different, I like doing fashion work because there is a certain freedom and license, which I think also causes a lot of problems with fashion; it becomes quite quick and you’re wanting to make things very quickly, the shelf life of work can be quite short. With my personal work, I am addressing my own experiences. But I’m also learning that they inform each other. I learned technical matters through shooting for fashion which helped me realize my personal work, and the issues that I address in my personal work seep through to my fashion work.

Quinn by Rydel Cerezo.

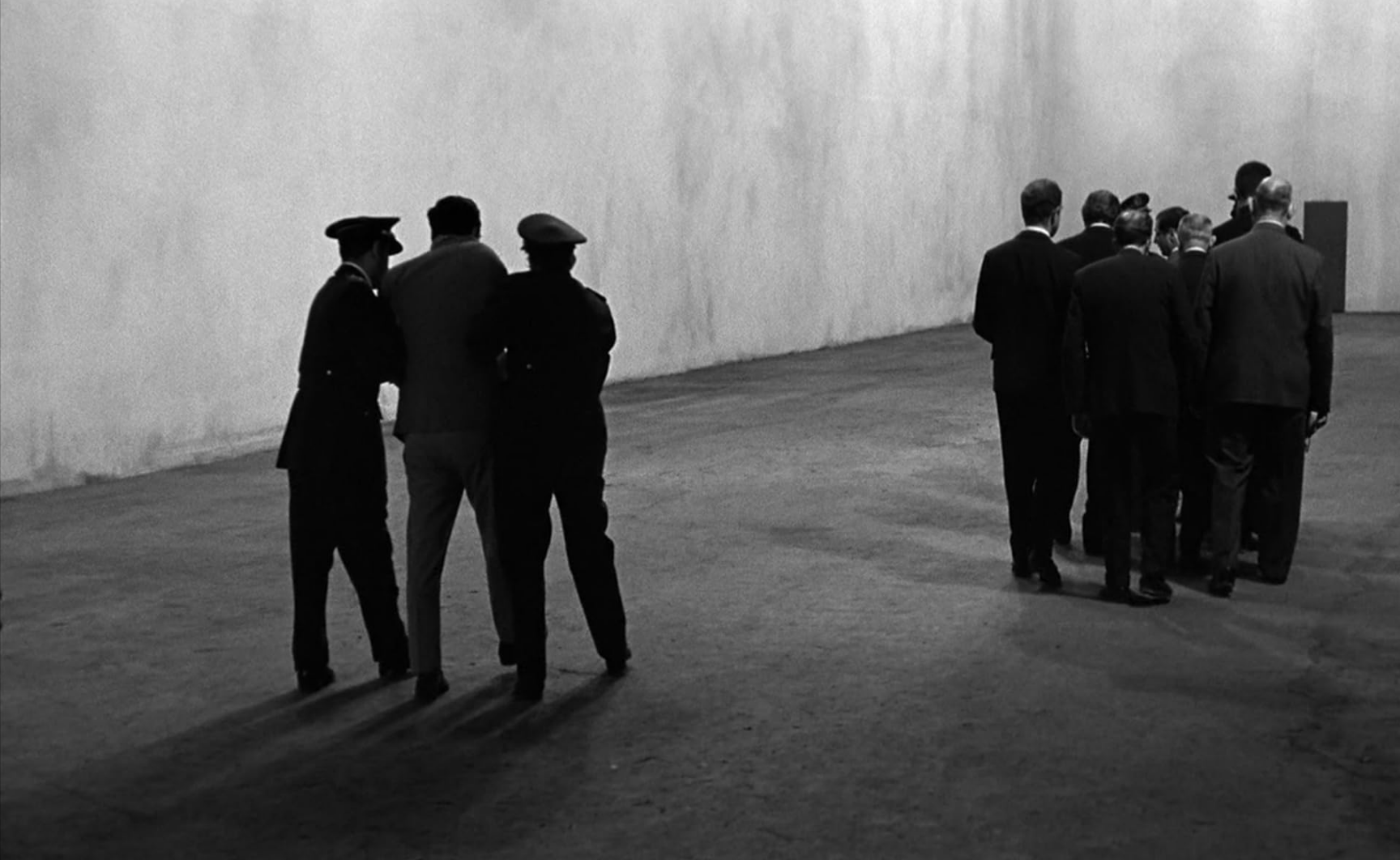

In his series Heirs (2019), the photographer credits the sensibilities he learned from working with modeling agencies and fashion publications as essential to the process. The photographs investigate a dominant, white masculinity recalling nostalgic typifying forms of visual culture. The series actually stemmed from a fashion-based photoshoot that Cerezo saw had the potential to become a larger project.

AR: What are some of the things that influenced this series?

RC: Photographer Collier Schorr. Her practice sees both art and fashion, and she talks about the experience of being in both spaces at once. In Heirs there’s this idea that to desire and to be desired live in the same spaces, especially through a queer experience. I was also watching Golden Age films, and even advertising in the 50s and 60s, imagery that was made post-war that has left such a resonance to our sense of desire and attraction. I was interested in how the body could be very white but also very queer. For the Cowboy in particular I was thinking of references like the Marlboro Man, the movie Giant, and Brokeback Mountain. The cigarette photograph which I titled Leather, for me has that history of Robert Mapplethorpe and also James Dean. I was thinking of all these postwar tropes or canons that set the precedence. I don’t think I’m making any new images really, I’m just appropriating them and putting them in a certain space so we can investigate them. The way I’m putting them together allows people to investigate further.

From Heirs, 2019.

AR: What are some of the techniques you used in putting images together?

RC: I was utilizing repetition because I think it’s very visually interesting, but I’m also aware of its history in ethnographic photography to sort of categorize or calculate “uncivilized peoples” bodies. I think I was trying to see if I could also calculate a white, male body for myself to further understand it, and not only look at it under a queer light but also under a racial light. Obviously it’s a failed experiment which is what I’m interested in, failing in that way purposefully and making that typography for myself to point certain things out.

Heirs, 2019.

AR: With your work, and these two series in particular, I see confrontations to institutions and yet there’s a sensitivity to the photographs. We’ve thrown around the term “tender confrontations,” do you agree with this term?

RC: Queer artists in the past have had violent experiences and created violent works regarding the church, which is very valid. In terms of addressing my own personal experience I’m not saying it wasn’t violent, but I’m also not saying it was only violent. I still pray and I still believe in god, and I think this inability to escape the church is informed by intergenerational trauma that is transferred. The church is still a space people congregate in and a sacred space that needs to be respected, and in regards to confrontation, I realized that I was putting myself in situations that were uncomfortable to me, so when I was going in there I wanted to do it in a way that was still sensitive.

In Heirs I was confronting the aspiration to whiteness and my proximity to white maleness, which is why I like “tender confrontations” because it’s a way for me to step into these spaces in a way that is still sensitive, because I don’t think it is one way or the other, my relationship to these things is very nuanced and complicated.

AR: In the spirit of nostalgia, is there any advice you would give to young Rydel, back in first year of art school?

RC: Focus on your grades a little more. If anyone is reading this also, don’t be afraid to build a (professional) relationship with your instructors, see them not only as your instructor but as a person you can communicate with outside of class and ask for their advice.

AR: What about advice for someone who’s just graduated art school?

RC: I think the hardest thing out of art school is to continue your practice; try to do your best to make situations and spaces for yourself that allow you to healthily create work and to continue your practice. Mental spaces and routines that make you mentally and physically healthy are very important. Seek opportunities on social media, be open to allot time to applying to get your work into the spaces that you want to get your work in, you can even think about it as an exercise for yourself to take off some of that pressure.