Sell Out, A Series: 5 Questions with Fay Nass

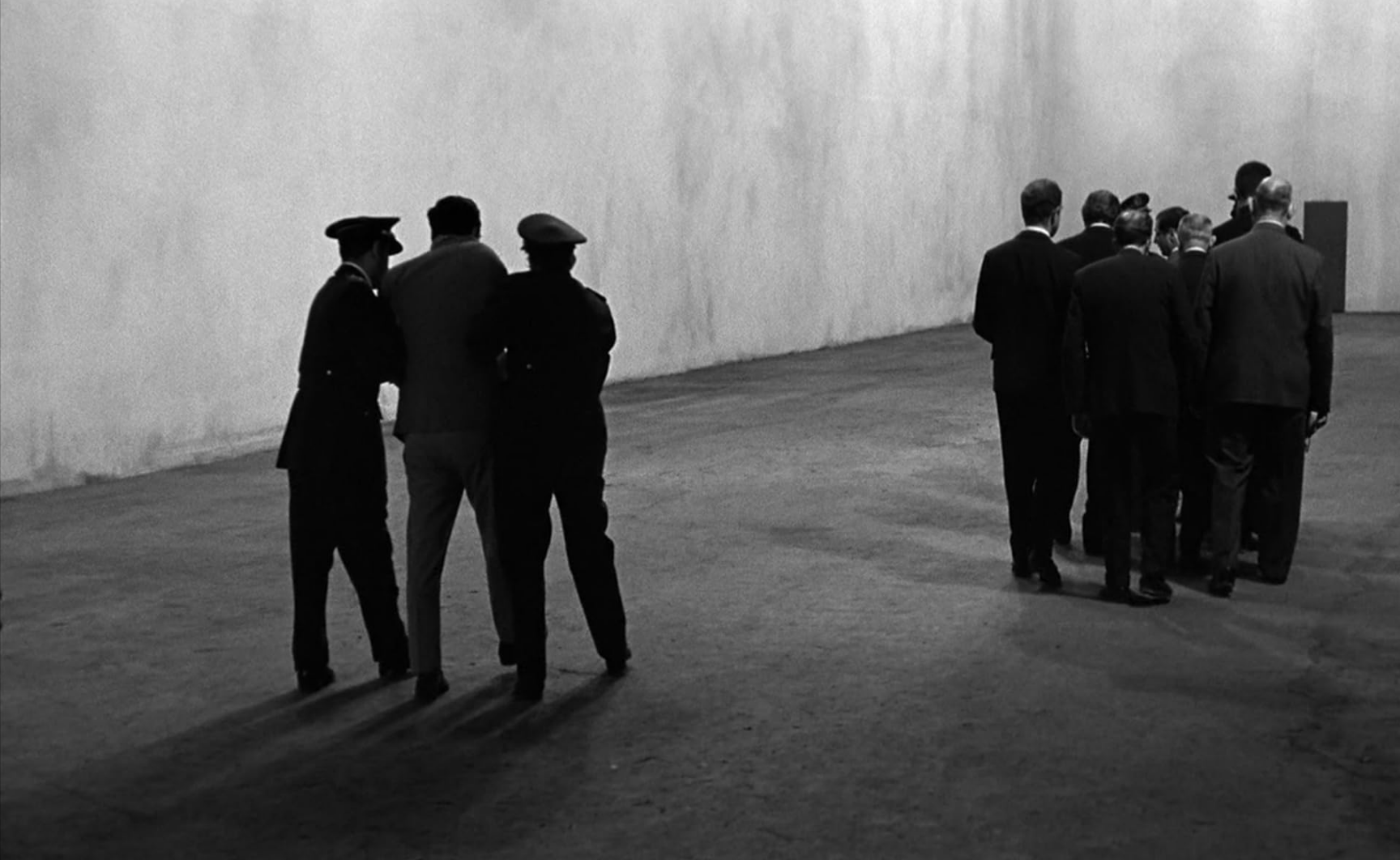

/Sell Out is a series by interdisciplinary artist Angela Fama (she/they), who co-creates conversations with individual artists across Vancouver. Questioning ideas of artistry, identity, “day jobs,” and how they intertwine, Fama settles in with each artist (at a local café of their choice) and asks the same series of questions. With one roll of medium format film, Fama captures portraits of the artist after their conversations.

Fay Nass (they/she/he) is a director, dramaturg, and community collaborator/devisor. They are the executive artistic director of The Frank Theatre Co. and founder/artistic director of The Aphotic Theatre. Visit them at www.thefranktheatre.com and www.aphotictheatre.org.

Location: Matchstick Yaletown

What do you make/create?

I create a lot of different kinds of work. My masters is in Interdisciplinary Arts. I work primarily in theatres, but what I make is often trying to deconstruct the form and look at new ways of telling a story. I use a lot of multi-media and cinema to look at theatre through the lens of the camera, as well as working with community participants who come from different backgrounds, and not as much through a formal training in theatre. I look at how the way we tell stories depends on how we think and our different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, and how to bring these different ways of storytelling – through content and form – onto theatre stages, into galleries and exhibitions, as well as through cinematic experience.

What do you do to support that?

I’m lucky that I lead two companies in Vancouver, which gives me the opportunity to imagine this kind of work through annual programming or a project base. I work a lot with BIPOC and first-generation immigrant and refugee communities. I do a lot of work as a devisor, which basically means that I think about a concept, or an idea, through community collaboration work with folks that have had those lived experiences, and then, with my own expertise in those field as a theatre director/writer, I bring those stories into life and kind of weave them together. A lot of the projects I do start with this conceptual idea that then, eventually, through working with the community, kind of manifests itself into a form of theatre, film, or exhibition in a gallery.

How I make that happen is through government funding, grants, and in my position at The Frank Theatre Co. I get a chance to produce a lot of annual programming, which allows a more sustainable practice of bringing these kinds of visions and thoughts into life.

Describe something about how your art practice and your “day job” interact.

I’m also an educator and scholar, so I teach sometimes. I teach at SFU English Language and Culture. In the past six years, I have been lucky to say that my day job and artistic practice dance in tango with each other.

My day job, really, as a leader, or running a company, is a lot of administration and budgeting and everything, but it’s always in relation to the creative projects that I’m imagining, so it doesn’t feel disconnected. My artistic practice is primarily in directing, but also in collaboration through devising. I can manage it because I have the opportunity to be the art director, to have a salary, and also to be able to have freelance work, as well as the work that we do through The Frank.

It’s lucky, but it has only been lucky for the past six years since my position. Before that I was teaching, and teaching was my main source of income, and I was basically applying for grants, hoping to write and create projects through grants.

What’s a challenge you’re facing, or have faced, in relation to this and/or what’s a benefit?

Since I was probably five years old, I knew I wanted to be a theatre director and writer, but I never thought that I wanted to deal with operation budget, grant writing, leading a company… you know, there is beauty in it, but also there is fatigue and exhaustion. I want to sit by the beach, or under a lemon tree, and just think and imagine ideas into life. I want the pace of my life to be much slower than it is.

As an artistic leader, you’re dealing with policies, managing your team, reporting, writing grants, budgets, and financials… I don’t know how I became good at it, because my own personal bank account is in such a horrible state. Somehow, I guess living in Iran for sixteen years, I was not as shitty as I thought I was with math and budgeting in terms of the company. I feel like there is this space in which sometimes what we are good at ends up being what we do, but it’s not necessarily what satisfies us, or gives us stimulation or inspiration. I feel like I’m good at managing, I’m good at leadership, but it’s not necessarily the space I want to be in all the time. I much prefer to just write and collaborate and create projects and imagine.

The biggest challenge is fatigue, exhaustion. Sometimes, if I have one day off, I wake up, and there’s like thirty emails that say, “Urgent!” I think the reason I love being an artist, I dreamt about being an artist, is because nothing felt that urgent. You take your time and your process – fight for your values, politics, and beliefs – because you want to make an impact rather than responding to something so immediately. That is the biggest struggle. How to maintain the energy to shift your mentality from a kind of administrative position as an artist leader to a creative position, how to balance those things.

I think that challenge was prominent in The Café project we just did with Aphotic Theatre. The Café was something I wrote the concept for ten years ago, and through Aphotic, I partnered with Itsazoo Productions – they have more experience with site-specific theatre. It took about six years for a company to take interest, and Itsazoo was the first one. I was the curator, writer, co-director, and co-writer of one of the pieces within it. I have an amazing board, and they were all like, “Yes, this is a great project!” I don’t ever look at art transactionally. To do a piece that involved nine playwrights, fourteen actors, and a limited audience of twenty-five to thirty…It’s a financial box-office failure, right? But I really wanted to bring that to Vancouver, for people to experience these concepts, and to be able to be in close proximity with these stories they haven’t heard – having that permission to be a voyeur, to break that form of being in a theatre, to experience a different relationship between audience and performers. When I think about it through a logical artistic director’s brain, this project should have been at a much bigger venue, with one hundred audience members, and tickets at fifty dollars instead of twenty-five. Even though the show was sold out, we were always in deficit, so I think those are the challenges. How can we create art that is pushing the boundaries without constantly putting the hat of an accountant administrator on?

The main benefit is still a salary – even though, when I talk to my friends in different fields, I’m overworked and my salary is not much. During the pandemic, a lot of artists had no job – to have a salary with Frank, I was able to, frankly, not be homeless. I don’t have any financial support from anywhere else, so the pandemic was like a wake-up call to how close we are, as artists or art and culture workers, in many ways, to not having a home. To have my day job was definitely, during the pandemic, something that I appreciated a lot.

And then also, to have the power to imagine and be able to push some of the visions that I have and the ways that I want to create – the processes, the pedagogy – and to bring all of that into the way that the company is run, and the way that we create work, and the work that we do. I feel it is a huge privilege to be able to be in a position of power where you can actually implement the things that you always dreamt, and hopefully now you can make those practices something that can also influence the sector as a whole. I feel very good about that.

Have you made, or created, anything that was inspired by something from your day job? Please describe.

At some point, when I was much younger, like in my early twenties, my day job was giving out newspapers. I was still in university, first or second year, and a lot of the things I would see in the city, the injustice really of class and community differences – even from station to station – was often influencing the projects that I was doing. I can’t say if my day job now has influenced any of my projects directly, but I can say that my everyday life – in terms of seeing and dealing with a lot of obstacles that people of colour, queer, non-binary people face every day, or seeing the lack of artistic directors in Canada who occupy the same body as me or many of the intersections that I am a part of – has definitely influenced the kind of work that I do, or the lens which I put into the work I create. I cannot say thematically it has influenced any of the projects directly, but I think it’s definitely a sensibility that is there; everyday life, or the job, or who is occupying what kind of space, what are the voices of people that are missing in these spaces… that is very prominent and influences my ways of thinking and the kind of projects that I do.

In a more specific way, when I was doing my master’s thesis and sitting in coffee shops, the concept of The Café directly came from what I was exploring during my master’s, which was around the idea of proximity and erotica spaces. What is erotic? I was basing it on a book by Dr. Laura Marks in which she talks about what is erotic through the lens of the camera, or in general the space of oscillation between giving and receiving, that space in-between. That it’s not about space, it’s about tension.

I was really focusing on that tension, and being in coffee shops, writing my thesis every day, I was seeing how that tension exists in the space. How so many people are sitting so close to you, talking about certain topics or ideas. How this neutral space, a coffee shop, is a space where a lot of personal and political conversations happen. In theatre, we often try to say we are pushing the boundaries of these conversations, but a lot of neutral spaces are actually so activated with those realities. I was directly influencing The Café project. Every day, I was going to Nelson the Seagull on Carrall Street. I was amazed by the diversity of people, stories, and languages, and how the way that you locate yourself, while continuing with these social agreements that you’re not eavesdropping, produces an erotica space. If two queer people walk in, then I’m already noticing, “Oh, there are two other queer people in this coffee shop,” and there is something that is activated in that space. I really wanted to recreate that in something that is site-specific immersive theatre, and that’s how The Café came to life. I can’t say it was directly related to my day job, but I guess, at that time, being a master’s student was my day job.

Angela Fama (she/they) is an artist, Death Conversation Game entrepreneur, photographer, musician, previous small-business server of many years (The Templeton, Slickity Jim’s etc.). They are a mixed European 2nd-generation settler currently working on the unceded traditional territory of the Coast Salish xʷməθkwəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh Nations.

Follow them at IG @angelafama IG @deathconversationgame or on their website www.angelafama.com