Interview with Poet Gregory Scofield

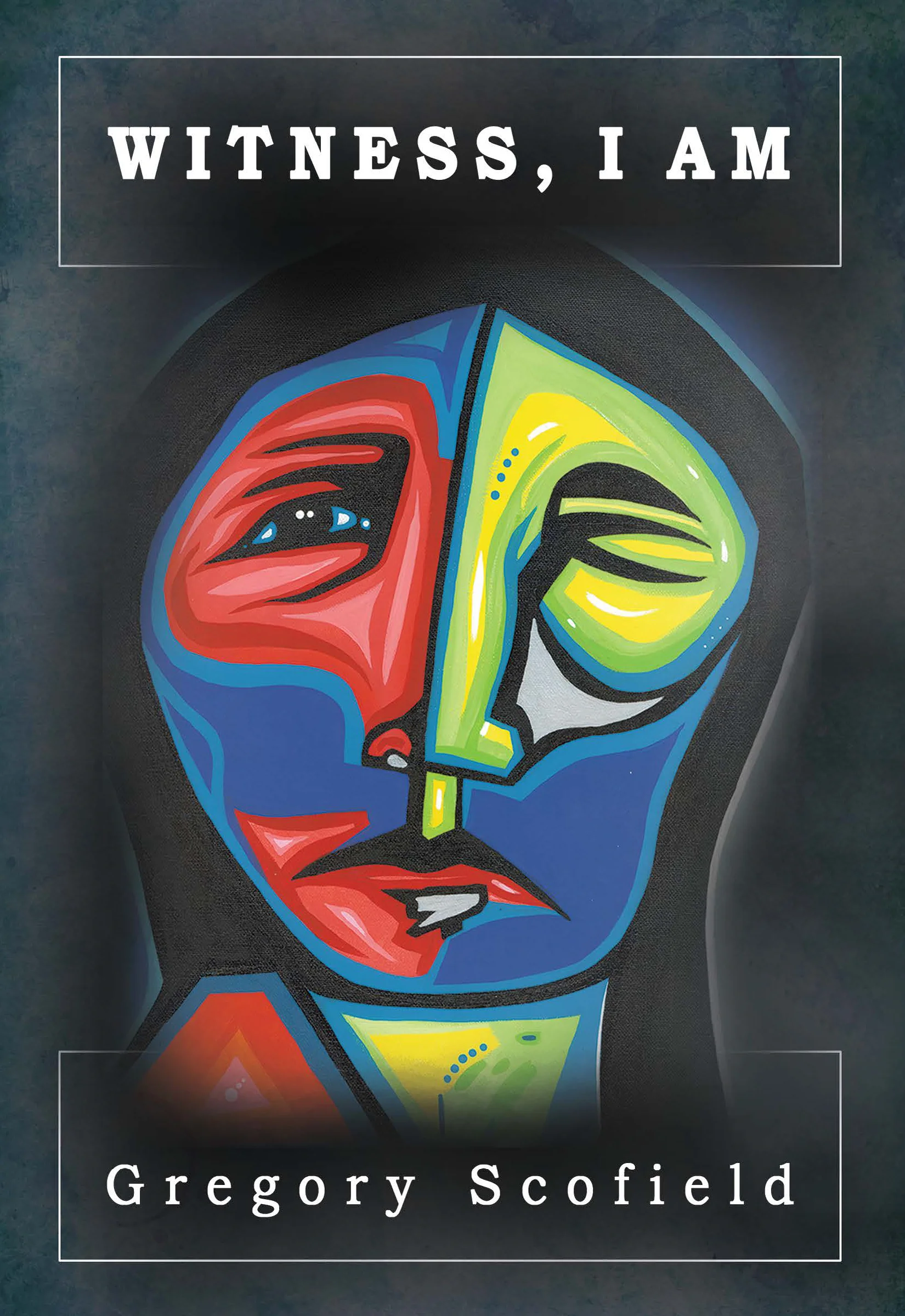

/Gregory Scofield's latest collection of poetry, titled Witness, I Am, was recently released by Nightwood Editions. Earlier this month, Scofield accepted the Latner's Writers' Trust Poetry Prize for his work. He will be launching this award-winning book in Vancouver on November 25. Here he is in conversation with writer Charmaine Li.

Charmaine Li: “Muskrat Woman” is a three-part poem honouring missing and murdered Aboriginal women, through the retelling of a (re)creation story. Can you speak to how or why you came to frame the book’s theme in a creation story?

Gregory Scofield: That particular poem, “Muskrat Woman,” actually began about two years ago when I was the writer-in-residence at the University of Winnipeg. I was thinking about one of our sacred stories, and “Muskrat Woman” just showed up one day. So I just began writing.

For a number of years, I have done a lot of advocacy work around the issue of missing and murdered Aboriginal women. I actually came to that issue from a very personal place; I lost my auntie in 1998 to a homicide. Like many of the Indigenous families that have lost women in their families, we were met with an incredible amount of that systemic classism and racism a lot of Indigenous people face (especially around missing and murdered women).

So, looking at one of the old creation stories which “Muskrat Woman” is based around, I wanted to take that story and re-imagine it. I wanted to re-tell that story.

In the original telling, the three characters of Muskrat, Otter, and Beaver are male, and Muskrat is the only one in that story able to get a piece of the old earth and have the world recreated.

So in my telling—my re-imagining—I wanted Muskrat Woman to be female. Basically, the re-imagining and re-telling of that story is from her perspective, and is a long meditation on her talking about how, in the recreation of the new world, she wants it to be different for her sisters.

CL: Throughout this collection, there are numerous references to Cree phrases and an attention to sound and rhythm. Does this style come from the influence of traditional storytelling?

GS: It comes from a few things. It comes from traditional storytelling and from growing up with those stories. My auntie was a wonderful storyteller and I was very fortunate to not only learn the Cree language from her but to grow up with a knowledge of those stories. So the style is very much story-driven and based upon the rhythm and sounds of storytelling.

I also grew up with a lot of music, and that’s something I’ve always found myself incorporating into my poetry. Probably since I began writing, I’ve incorporated those rhythms, those sounds.

CL: As a writer myself, I often wonder what my role in society is. The poem “Poet” describes a character who discovers unexpected duties as someone with that job title. How are poets perceived in Cree and Métis culture? How are their roles in those societies different from mainstream, western, Canadian culture?

GS: That’s a wonderful question! I think one of the answers is that we’re living in a really exciting time for Indigenous writers right now. You can’t really separate the poets from the other writers. Really, Indigenous poets, fiction writers, playwrights, and non-fiction writers all very much coming from a storytelling tradition. They come from a place of observation, re-telling history, re-organizing, and re-telling history, specifically re-telling the historical narratives that are very damaging for Indigenous people. So, really, the way I’ve always personally considered myself in relation to Indigenous writing—and specifically to poetry and as a poet—is this: I am one small singer in a community of powerful singers.

CL: Two poems that really struck me were “Despite” and “Credible.” They speak to resistance and perseverance despite what happens and how much we’re silenced. Is this the poet’s duty?

GS: Absolutely. Generally, as writers, as poets, as storytellers, our job is to keep those histories and stories alive. Of course, perseverance and resistance are an integral part of telling those stories.

CL: I think it’s interesting how social media has influenced storytelling, and especially how it has impacted our perception of contemporary Aboriginal social issues. Can you speak about your own online activism, on Twitter?

GS: Just to give you some background on my Twitter activism: when I first took to social media about three years ago, I made a decision to not simply add to a continual dialogue, chiming in my two cents whenever I felt like it. I wanted to have a reason––I wanted to have a purpose in using my Twitter account.

So I decided to use that account for what I call “Name a Day.” The Name a Day Tweets feature the name and picture of an Indigenous woman who has either gone missing or who we’ve lost through violence. The Name a Day posts are really one of two things: they serve as a PSA (I really hope that people are using that account to locate missing young women), and they add to the awareness campaign for missing and murdered Indigenous women.

One of the things I try to do with my public voice is bring this issue forward to people who see those images, or read those statistics on TV or the news, but are not really connected to them.

Whether I’m doing keynote addresses, or what have you, I talk about my auntie, I talk about my relationship with her (I grew up with both my mother and my auntie). I talk about losing her. I talk about the process I’d personally gone through with losing her, because I want that issue to be humanized. I want that issue to be standing in front of people—a tangible person standing there, talking about this experience.

CL: Any thoughts on the Standing Rock phenomenon?

GS: With online activism, we’re living in a time right now where we can virtually all be connected, where we all become responsible for the outcomes of situations. We become responsible for changing the trajectory.

For example, with Standing Rock, I know in the Indigenous online community, people have been doing all kinds of activism. People have been going down to North Dakota physically, with their bodies. Other people have been using online options to raise money for those who are on the front lines. Artists are also writing about what is happening. I think one of the incredible things here is that as activists and artists, as storytellers, politicians, and actors, people are bringing this issue to a much larger platform. People are making this issue relatable for everybody.

One of the things that is so important with what’s going on at Standing Rock right now is the idea that, literally, water is life. And without water, we cease to exist. Water doesn’t know a colour: water is not red, water is not black, water is not white, water is not yellow. So really, we all have a responsibility to protect water, no matter how we come to it.

CL: The only prose poem is “Almost Gone,” written about the speaker’s institutionalized mother and her perseverance in keeping her identity. When do you choose to write prose poems as opposed to verse?

GS: I don’t really choose the form of poetry that I’m going to write in. As I was saying, I approach poetry from a storytelling perspective. I always leave it up to the story to decide the way in which it wants to be told. Sometimes the story wants to be told with music, sometimes the story wants to be told with sound. Sometimes the story just wants to be told in a minimal way.

CL: In “Prayer for the Man Who Raped Her,” the speaker entertains thoughts of wishing bad things upon their rapist but instead decides to pray for the peace of his female relatives. This poem reminded me of Canada’s conversation around Truth and Reconciliation. What is “Reconciliation” to you?

GS: A lot of people are still trying to figure out, what does this mean, what does this look like, how does this affect me, how can I be a part of this? For me, my act of Reconciliation—my ongoing act of Reconciliation—began in 1993 when I began writing, and poetry has always been my act of Reconciliation. And I continue to use my writing, my poetry, as acts of reconciliation.

CL: What’s next for this collection? What are your goals? What should readers take away?

GS: My greatest hope is that “Muskrat Woman” becomes a ceremony that I hope people will choose to partake in. “Muskrat Woman” is a very layered story, a very layered poem, and there are many things that I’m still learning from that poem.

This poem is really a gift, if you will. It was my ceremony for the people in my community. It’s not only an honouring of our mothers, our aunties, our grandmothers, our sisters, our nieces, our cousins, our friends, but it is a layered piece that I hope people will find something of themselves in. Something of their own experiences and their own reality. The greatest gift of art, whether that’s literature or painting or dance, is to be able to show people a glimpse of themselves. So that is my hope with this collection, particularly with “Muskrat Woman.”

What’s important about that poem is a calling of names, a reading of those names, and alliteration and enunciation of those names. I’d definitely say names are bundles, and those names need to be carried in a very sacred way.

Gregory Scofield is of Cree, Scottish, and European descent. He was born and raised in the Lower Mainland and currently lives in Sudbury, teaching Creative Writing as an Assistant Professor in Laurentian University’s English Department.

Interview has been edited for clarity.