SAD Again: The Stars—Les Étoiles

/The Fantasy Issue was only the fourteenth ever published by SAD, and featured the first-ever fictional piece published by the magazine, which should tell you everything you need to know about author Ashleigh Rajala’s penmanship and incredible knack for whimsy. In the introduction of this issue, former Co-Editors Michelle Reid and Jackie Hoffart posed the question: “What can we dream into reality on our pages?”, and with the magic and hubbub of the holiday season rapidly approaching, I asked myself a similar question. As avid readers we are expected to relish in all the diversity that literature has to offer, and while I wholeheartedly agree, I will always have a little nook in my heart reserved for the weird and wondrous fabrications that fantasy has to offer. Here is where writer Ashleigh Rajala comes in.

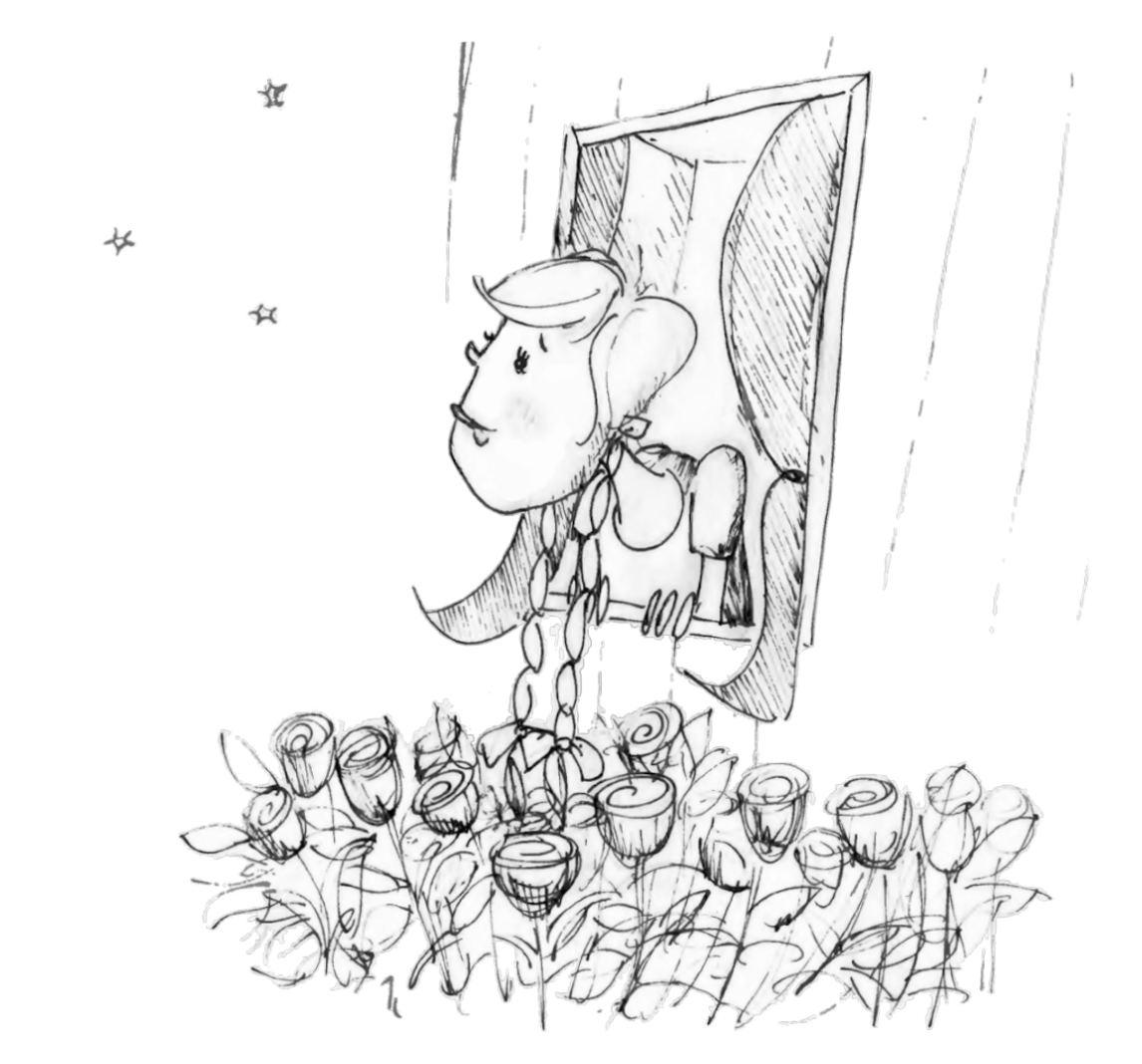

Illustration by Caitlin Bauman for issue 14: fantasy

As an award-winning author, Rajala has explored the realms of fiction, filmmaking, zine creation and role-playing game design, with her work being published in various magazines, zines and journals. These include—but are not limited to— Magpie Zine, Button Eye Review, Crab Fat Literary Magazine, ROOM and, of course, our very own SAD Magazine. Back in 2009, Rajala also wrote and directed a short film, “The Year Without Hockey,” which was selected for Hell’s Half Mile Film Festival in Michigan. But you can always discover these for yourself (and more!) on her website ashleighrajala.com, with some witty writing to be found on her personal blog sandpaperblues.wordpress.com.

While I have yet to be acquainted with the full extent of her work, in reading her short story I was at once struck by her ability to ground readers in her worlds with few words, facilitating an attachment with characters that may only exist for a short amount of time. Of course, there is always the lingering sense that their life continues beyond the constraints of the written word, which I consider the quality of a good writer. At the heart of the story is a young girl desperate to be seen, sure to connect with readers that may interpret her plight in their own way. This is fantasy, after all, and there is often more than one meaning to unearth here.

The Stars—Les Étoiles

Words by Ashleigh Rajala

Illustrations by Caitlin Bauman

Illustration by Caitlin Bauman for issue 14: fantasy

Just like Scarlett O’Hara, her dress was made from curtains. It was white now but it had once been purple.

A long time ago, before she was even born, the curtains had been selected for the living room because they matched the wallpaper perfectly. She grew up in a living room of purplepaisley. Everything was purple, actually. Her father liked it like that and her mother never thought to complain. But she, their only daughter, never really cared for purple. But they didn’t listen. And so purple it always was.

The last time she had a growth spurt, she outgrew everything she owned so her mother had to spend the morning sewing a new frock. (She was late for school but no one noticed.) When she returned home, she blended into the wall. Perhaps she would disappear into the drywall, get pulled into the foundations, and be left to stew for eons in the dirt under the house. A few years from now, would her father look up over his paper to her mother and ask, “Hey, whatever happened to our daughter?”

It was the only dress she owned. Always she blended in. She had hoped that growing would help. She always wanted to be bigger. And growing would mean a new dress. And so she wished she would be. She wished and wished but nothing ever happened. Little and insignificant she stayed. At dinner times she would pass the salt when requested and that was where she remained.

Then, one day, she heard a rumour: there are things upon which a person who desired something could wish. They were called “the stars,” or “les étoiles.” She liked both names and couldn’t pick a favourite. She wished every night now after she put herself to bed, “Please, les étoiles, please. I have grown so little these past few years. I want to be bigger. So big that no one can ever ignore me again. Please, stars, please. I want to grow and grow and grow.” She wished every night with her head poked out the bedroom window and her hair hanging down in tight braids brushing against the rose bushes below; she wished on les étoiles.

There was something special about one star, she thought. It flickered like the candle she once saw her grandmother carrying down the dark hall when the lights went out. It flickered blue and red. She smiled to herself and felt the cracks between her loose teeth with her tongue as she closed the window. The stars were special, she thought, they would heed her desire.

She knew her wish would be answered. And it was.

By the next morning, she’d outgrown the curtain dress. It stretched tightly against her skin, the seams bursting, the hem skimming far too high above her knees. Again her mother ripped another panel of curtains from the living room windows. Again she haphazardly stitched together a frock. (Again she was late for school. Again no one noticed.) Again her father sat at the dinner table, his newspaper stretched in front of his face, “Pass the salt.”

Again she poked her head out the window. Again her braids brushed against the roses. “Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

The next morning, she’d grown again. (She was late for school and still no one noticed.) “Pass the salt.”

That night, to l’étoile blinking red and blue, “Please, les étoiles,

please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

By the next week, her mother was setting her alarm clock earlier and earlier in preparation for the new dress she would have to sew.

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

Within another week, all the curtains in the entire house were not big enough to make a dress for her.

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

“Pass the salt.”

A week after that, she didn’t fit in the house any more.

A week after that, she didn’t fit in the yard.

A week after that, she didn’t fit in the local football pitch.

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

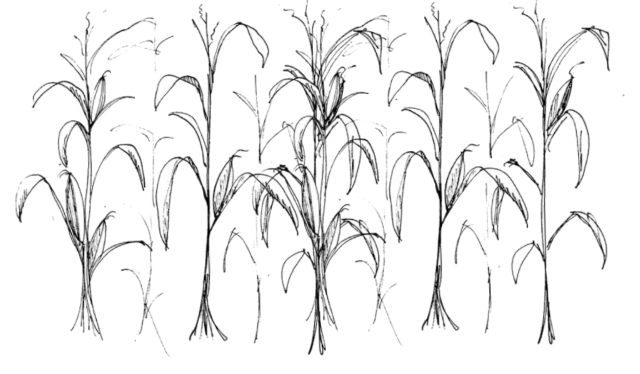

A week after that, she was sleeping several miles away in the farmers’ fields, the cornstalks making her pillow, the pumpkin patch at her ankles. She wore all the curtain dresses stitched together around her body. (The school eventually sent a letter wondering why she had missed so many classes.)

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

Her mother stopped sewing altogether. Whatever fabric she could find was lashed together with duct tape. They used sticks and wet rags to give her a daily bath. (The school claimed that the field was out of their catchment area and she should no longer attend.) But still she had not seen her father. The newspapers did not deliver to fields.

Illustration by Caitlin Bauman for issue 14: fantasy

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.” Her mother and the farmers gathered together with the sons and daughters who would take over their plots one day and dressed her every morning. The potato farmers hoisted on socks stitched together from a thousand potato sacks. The corn farmers wove their corn silk into rope and thread to bind the fabrics around her limbs. The blueberry farmers used their rakes to comb her hair; it took 10 of them four hours to plait her hair and tie the bows. Their field was directly under her; she’d ruined not only their farms but also the bottom of her dress. The curtain-dresses-frock was stained with a blue sweetness that cost more than her parents could afford. Her mother passed along messages from home that the newspapers issued columns reporting on the increase in the price of blueberries and why oh why could this have happened?

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

When the point was reached that her mother, along with all the farmers, had to work out a system of ropes and pulleys to get the curtain-dresses over her growing body, she made the front page of the newspaper. They came out in hoards to see her and this wooden contraption built around her growing body. Photos were taken in endless succession of the docks built up to her shoulders; of the toothbrush, like an oar from an ancient slave ship, which took six men to work; of the now-ragged curtain dress hanging in lashed-together shards from her expansive skin; of the patchwork fleet of tarpaulins strung up over her head; and of her face, freckles the size of hula hoops. They needed to back up nearly a hundred yards to get her in frame. The flashbulbs sparkled around her and she realized with glee that they noticed her. They asked her questions and questions. “How much do you eat?” and “How do you bathe?” and “Is purple your favourite colour?” They did not ask how or why she grew so large. And so she kept the secret of les étoiles to herself.

That was when her father came for the only time to the farmer’s field. He brandished the newspaper with her picture across the front, grinning proudly. He wore his best sweater vest when he came to visit. She stopped wishing. Even though she no longer needed to poke her head out a bedroom window, she stopped wishing. She wasn’t sure how many weeks had passed since that first wish had been granted, but it was then that she finally stopped growing.

She was famous for a week.

Then the fields fell back into silence. The farmers finished counting up the money they’d made from letting the reporters and sightseers park in their driveways. Her mother put her hands back on her hips. Her father returned home, the newspaper tucked under his arm once more. She tried to wish again, “Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I am not big enough yet.”

But nothing happened.

She never shrank again, but she had stopped growing. For years she stayed that size. For years she stayed in the farmers’ fields. She got to know their names, their histories, their dreams. The rains came. The rains went. The snow came. The snow went. The sun came back. The sun left again. The contraptions around her gradually grew more permanent. The seasons swung by: year falling into year springing into year, then falling again then bouncing back again. Metal replaced wood, polyester fleece replaced wool, industrial cables replaced corn silk.

Her curtain-dresses faded from purple to lilac to lavender to white.

The crops around her had long since withered. The farmers retired when their money went and nothing else could grow to replace it. The sons and daughters of the farmers—who had once planned on taking over the farms—married, had children, and moved away, leaving the farms behind. She heard occasionally how they went into the city. Eventually none of the farmers were left anymore. When her mother herself disappeared, her knees too old and rickety to row the toothbrush anymore, there was no one left to see her anymore.

That was the first night in nearly ten years that she wished upon a star again.

“Please, les étoiles, please, stars. I don’t want to be seen anymore. I’m sick of being seen. Please. I don’t want to be seen anymore.”

Years later, Stella, granddaughter of old potato farmers, drove near the fallow fields, remarked casually to her own grandchildren in the backseat of her jalopy: “Look ahead andyou will see a giant. I remember her when I was younger than you. She wore all purple then, but it’s white now.”

The grandchildren laughed, “Silly Grandma! There’s nothing there!” As the jalopy disappeared down the lonely, quiet road, the invisible giant let go her breath, sighing again, alone once more.

Illustration by Caitlin Bauman for issue 14: fantasy

Kirsten Danae: This story was published in SAD's 2013 Issue: Fantasy, and true to the theme abounds in whimsy and the sense of nostalgia often present in fairy tales. Where do you find inspiration for your more whimsical stories? And how has your writing process evolved since?

Ashleigh Rajala: For me, whimsy and nostalgia are so deeply entwined with each other. They’re both so complex emotionally: both are fun and sweet and playful; both are dark and sad and painful. I think almost everything I’ve ever written has been whimsical and nostalgic, in one way or another. Fairy tales are just a perfect way to combine the two. Most of us heard them as children, so reading or writing fairy tales as an adult is a way of communing with our inner child.

These stories are safe ways to explore dangerous truths; an exciting—and safe—way for children to learn not to go into the woods alone. Whimsy, then, is the sense of fun and play that we adopt when processing dark themes. It’s a type of gallows humour, really. In a way, fairy tales aren’t far from gothic horror; in both, the past intrudes on the present. We can be afraid of it or we can get nostalgic or whimsical and make friends with the ghosts.

If there’s any way my writing process has really evolved since 2013, it’s in that. I’m not afraid of the ghosts anymore. I’m much more intentional now, for better or worse. “The Stars / Les Étoiles” was a rare gift in that it seemed to come out fully formed. Most pieces from that time in my life read as half-baked to me now, like first drafts that somehow persevered without edits.

A huge part of what I’ve learned since is technique and discipline.I’ve improved my ability to pull myself up and out of a piece and read as an editor would. I think that sort of perspective just comes with time and experience, but most importantly, practice.

KD: You have written dozens of stories published across various magazines as well as a short film for the Ferndale Film Festival. What advice do you have for emerging creatives that want to specialize in short fiction or film?

AR: Short work is difficult, especially considering how much of the popular media we consume these days is long-form (e.g., novels, feature films or serialized television). We’ve internalized story arcs of this length so much that they’ve become instinctive; they feel like what a story should be. So now, when we write something short, we often find ourselves simply condensing what is actually a full-length story arc. I’ve done this so many times myself; so many of those early works of mine suffer from this.

It’s hard to know what a short piece should actually be about. It only needs to hinge on one incident; one small change in a character. To help internalize, I really recommend watching and reading tons of short works, especially older films and television. Short stories and single-story episodes or short films were much, much more prevalent in the middle of the 20th Century. I’m on a bit of a weird horror streak at the moment, so current personal favourites include the anthology series The Twilight Zone, anything Shirley Jackson, and the utterly brilliant BBC show Inside No. 9 (which I cannot recommend enough).

The last bit of advice I can give to any one in the creative arts is just to get connected! Other writers, creatives, and people who just like the same stuff as you are great, but all that really matters is that you have people in your life who give you space to indulge your interests and who support you and your work. You need space to be yourself, really. Whether this is a friend you have at work who listens to you tell them about your new story idea, or an online forum about a genre, or writing circle.

Writing is such a solitary activity, so feeling even a little bit like you’re not alone does wonders. You often carry something in your head for so long, even put it on paper and rework it over and over until it becomes a little flat and meaningless, but then just telling someone something about it suddenly makes it come alive again. People often say that we create art to express ourselves, but I think it goes further than that. We create art to communicate, to connect. It’s a way of making ourselves feel truly seen as ourselves, in that weird little way we can’t otherwise articulate.

KD: What has been the most important lesson you have learned as a writer thus far?

AR: The most important thing I’ve learned is that there’s a huge difference between writing your first draft and editing your second. I have pinned up on the wall by my desk at home a quote from Terry Pratchett: “The first draft is just telling yourself the story.”

You’ll probably write and rewrite over and over again before you reach a point where you just have to go “that’s good enough.” Nothing is ever “done.” There are no clear rules or guidelines for what “good enough” is; you’ll have to trust your instincts. What this process looks like is different for every writer and—even for the same writer—it might be different for every project!

KD: I have always felt that fiction has the power to convey deeper truths about the world we live in. What do fantasy, and this story in particular, mean to you?

AR: What I like most about fantasy and fairy tales is that we can build in so many layers of meaning. We’re communicating so many different things with seemingly simple stories. I always think of what J.R.R. Tolkien always said about The Lord of the Rings not being an analogy or metaphor for anything. It wasn’t meant to be allegorical; it was meant to be applicable. A fantasy or fairy tale is applicable. The meaning isn’t some puzzle to figure out, but a whole array of different potential meanings that different readers can simply intuit and feel rather than intellectualize.

Re-reading “The Stars / Les Étoiles” again thirteen or fourteen years after I wrote it really underlines this for me. I can see the conversations I didn’t realize I was having, especially with all the women in my family. In ways I hadn’t even begun to unpack yet at the time, this piece spoke to my insights into their lives, how the world changed over their lives, their intergenerational trauma, and to their desire to “be bigger” than the space the world had carved out for them.

When I wrote this, I felt like the little girl, desperate to be seen. I always knew that the girl wishing to be invisible was the “right” ending, even if I couldn’t understand why at the time. But I get it now. The girl never needed to be seen (to perform, as it were) but needed to just be able to take up as much space in the world as she needed (without being an object of spectacle). She needed to have space to just be. Then, I was the little girl; now, I’m the invisible giant. It’s a happy ending!

KD: Of course, I have to ask, what are you working on now?

AR: I’m currently working on a few different things, including developing a roleplaying game, but the project I’m most in the weeds on right now is a contemporary gothic novel about a chosen one and his partner who saved the world, but ten years later struggle with a not-so-happily ever. Sure enough, there’s a murder in their otherwise cozy small town and the chosen one is soon the prime suspect.

This all came out of a murder mystery dinner party game I wrote to play with friends a few years ago, but I was never able to let go of the characters or the world I created. To me, that’s a sign there’s something there. It’s been multiple drafts and iterations since, but I’m still telling myself the story. I can’t wait to tell it to others!

Kirsten Danae (she/her) is a writer with a passion for film and the occasional excess in caffeine. She grew up in Mexico before moving to Vancouver to study English and Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia, and in her free time enjoys watching and reviewing movies so she can write one herself someday. Follow her on IG @keeks_diner