Zanj Hegal la: Colonialism, Filmmaking, and Attempts at Accountability

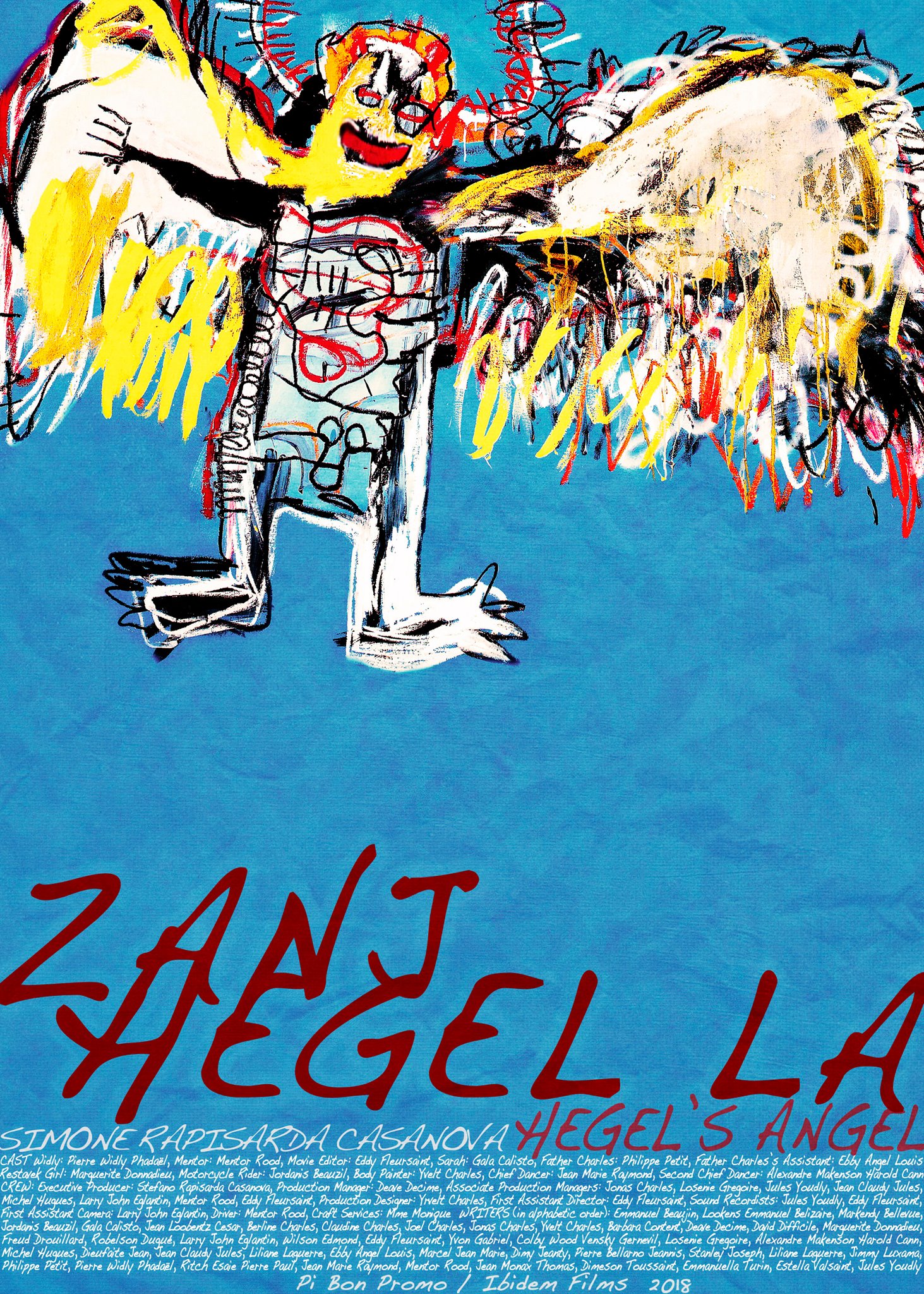

/Zanj Hegal la, image via The Cinematheque.

Simone Rapisarda Casanova’s third feature film, Zanj Hegal la, (Haitian for Hegel’s Angel), mirrors his previous works’ hybrid nature of documentary and narrative as it explores the mundane yet mystical world of a young boy named Widley. Coated with imagery of the local Haitian practices of Vodou and Kanaval, this reflexive narrative was created through direct collaboration between Casanova and his film students from the Ciné Institute of Jacme. The film simultaneously questions the ethics of its ethnographic filmmaking, while also exploring the aftermath of colonialism in Haiti.

Zanj Hegal la begins with epic choir music over striking shots of people climbing off small boats towards the land. We see a young black man carry a white woman on his shoulders as he hikes through the ocean waters to the nearby sandy beach. Just as you begin to accept this bombastic opening, the rug is pulled out from under you as the editor of this film within a film is seen discussing his work with his young friend Widley. Here, we are quickly introduced into the film’s constant reflexive nature. Casanova describes this style as when a filmmaker “makes the spectator aware that he is watching a film,” a tool he uses to great advantage to both explore the boundaries of the medium, and to call to question the ethics of a white Western filmmaker documenting the lives of people of colour from developing nations.

Both of Casanova’s previous two films are ethnographic works centered on the lives of small communities in foreign countries. He explains that when shooting his debut feature The Strawberry Tree in Cuba, he approached it with the mindset that “every person that goes to a foreign country, especially a Westerner going to a third world country with a camera, is an idiot. So I wanted to create a record of this with this film. I put myself behind the camera, and played the role of the idiot.” This directorial performance of idiocy can be seen throughout Zanj Hegal la, both directly as characters refer to a mysterious film director as a “funny weirdo,” and indirectly through scenes with clumsy craftsmanship during the mise en abymes.

Casanova acknowledges that this reflexive filmmaking and recognition of cultural ignorance does not clear him of all ethical questions. He proclaims that even if the medium of film itself is exploitative, that he tries “to counteract that with action.” He states, “I try to make films where everyone involved in their making somehow would benefit. The only way to counteract the [exploitation] is for me as a filmmaker to not accept the limitations of the medium, and do something personally to counteract that.” He listed many actions he takes outside of the filmmaking processes to attempt to bring balance back to his subjects, such as giving them final approval of edits and returning any money he may receive from screening fees back to them. Aside from the ethical reasonings behind these choices, Casanova also stated, “I take care to make films with people I think I can fall in love with [...] I don’t think I could ever make films like other filmmakers do with subjects they despise or don’t feel a connection with. I think because I am a shy person, I make films with people I would like to befriend.”

Aside from these ethical qualms, Zanj Hegal la documents a community left stranded as they continue their existence in a world that one character jokingly calls “post-colonial.” The feature includes strings of many different stories, including an unfinished short about a stereotypically malicious white priest, and scenes which seem to call to traditions and understandings based upon Haitian Vodou. One of the best moment of the film is a scene featuring a Vodou dance ceremony; a red glow washes over a Haitian woman performing a mesmerizing dance as she stares into the camera’s lens.

The element that ties the film together is Widley. We see him as he watches over his friend’s editing work, and when he goes about his regular days, and these everyday moments are where the heart of the film lies. These scene are neither epic nor heartbreaking, but portray a banal or playful tone. Casanova explained, “having grown up in the countryside [of Italy], normal people always laugh at everything. The serious people are somewhere else. I can not make a film about the people that I love and am comfortable with—these situations they are in, they are dire—it would be betraying them if I wasn’t able to capture them and their humanity.”

Zanj Hegal la attempts to present a new imagining of contemporary Haiti that embodies both its histories of colonialism and varied cosmological understandings. The film succeed in raising questions about how one might portray a culture that is not their own, and in presenting a lead whose life we are able to fall into. However, though the film attempts to embed stories of Vodou and Kanaval with the written collaboration of the Casanova’s Haitian students, it falls short in producing a clear vision of these moments and how they may connect to the remaining strings of the work. In the end, the film allows its viewers to rethink stereotypes about Haiti and its peoples while pushing the boundaries of documentary filmmaking.

The Cinematheque is running The Spirit of Place: Simone Rapisarda Casanova now through January 25th. For more info and tickets, go to thecinematheque.ca.