SAD Again: Bein' Gay, Doin' Crimes

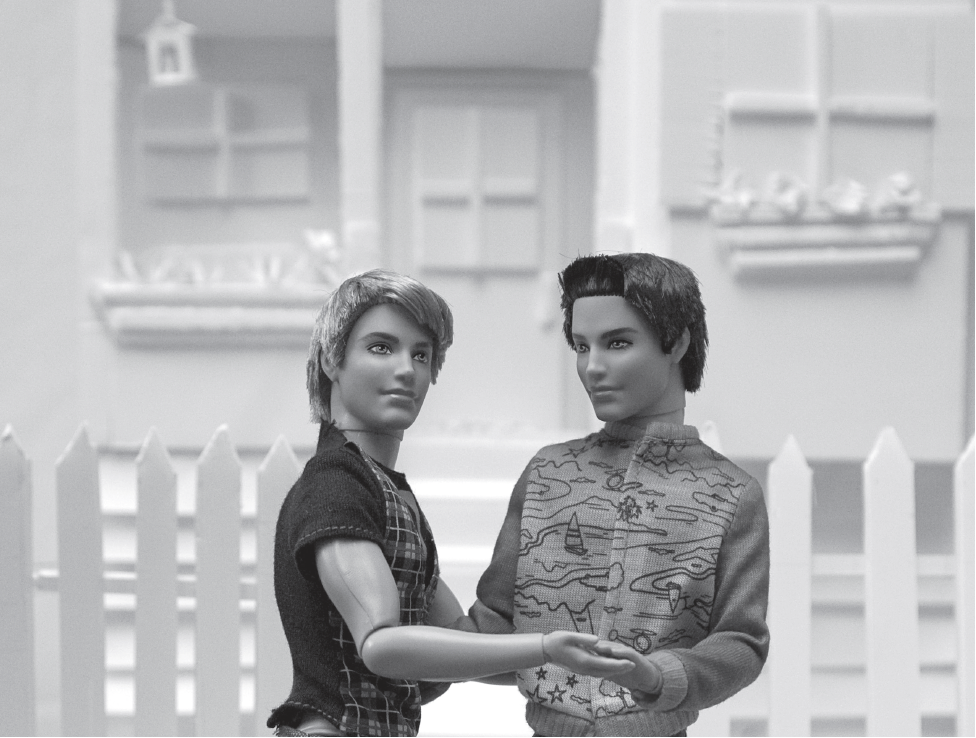

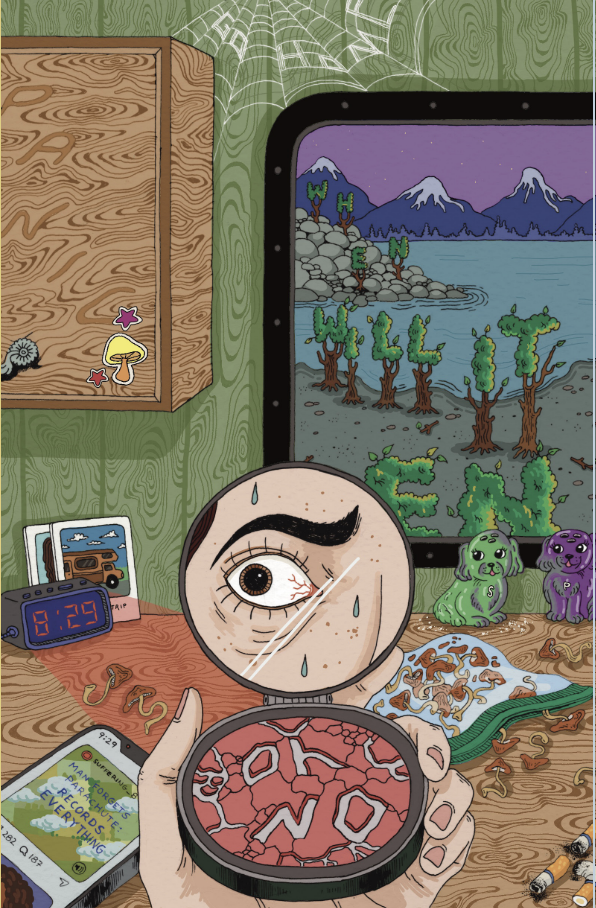

/Art by vincent lins for the sex issue

SAD Magazine saw its first issue hit the shelves in 2009, and 38 issues later we are continuing to build on an amazing community of creatives. With new artists, photographers, designers, writers, and many more making their debut on the magazine each year, the amount of material to get through as a SAD reader can be overwhelming, but fear not because SAD Again has you covered.

I have been diving deep into the archives to dig out some old treasures, and with a lot of cooperation from past print contributors, I am happy to present you with the first in a series of pieces honoring their hard work, and how far they have come since their SAD days.

Sad again? Read SAD again.

Jordan Johnston was one of the contributors for the Sex Issue, boldly delving into the realm of identity and privilege. I was immediately intrigued. In his piece, “Bein’ Gay, Doin’ Crimes” (a better title I couldn’t have come up with myself) he does not shy away from the struggles that queer people face in a heteronormative society, highlighting the need for rebellion as a means of standing up for their rights. With Pride having just come and gone, I think this is a great reminder of the lengths queer activists have gone through for their community, and the lengths people go through to define themselves.

Bein’ Gay, Doin’ Crimes

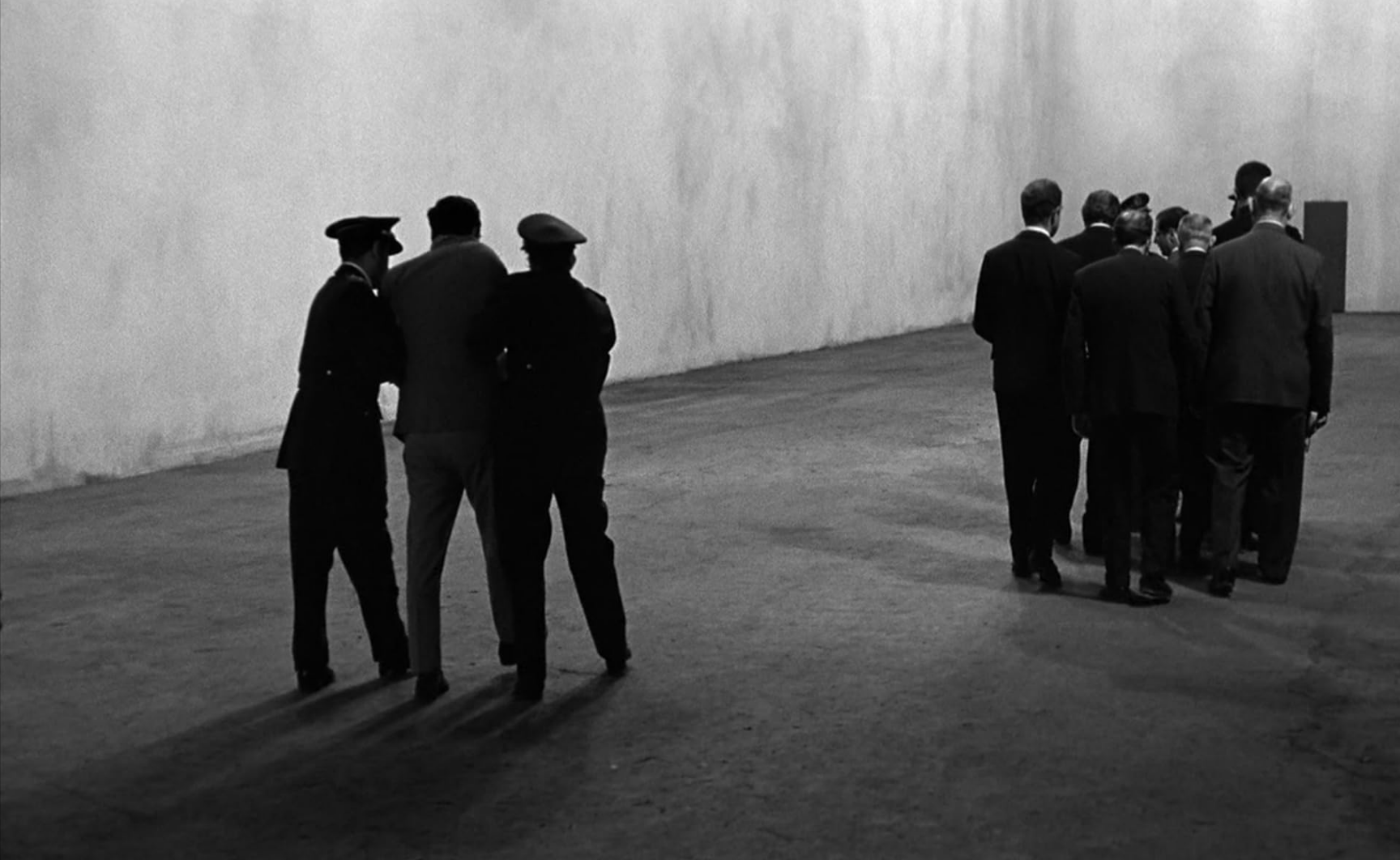

On crime, deviance, and privilege

I’ve always had this curious desire to spend a night in jail. Not because I dream of committing grand felonies—it just feels like an experience I should have as a queer person. There’s a long history of LGBTQ+ people putting their lives and reputations on the line to fight for their rights, from Stonewall rioters to HIV/AIDS activists to same-sex marriage advocates. It may come as a shock, but society is pretty heteronormative, so part of the queer experience is being a rebel just by existing.

The trouble is, I’m a bad rebel. No, not bad as in a bad bitch kind of rebel, just bad in general. When I think of getting arrested, I have this fantasy of being dragged away for protesting human rights abuses by a corrupt government, the kind of clear moral imperative I’d like to think I wouldn’t hesitate to act on. This fantasy is all very glamorous, somehow, and I never imagine spending more than one night in the clink.

I’ve never actually attended a protest where there was any real risk of arrest, and I have a feeling attending a demonstration just to get my Jane Fonda moment is a dreadful reason to get involved in something. Breaking the rules has never been my strong suit. As a kid, I gained acceptance and praise from adults by being well-behaved, and I loved feeling morally superior because I was good at following instructions. Don’t judge me too harshly—I was, of course, terrible at sports.

Though for many years LGBTQ+ folks broke the rules just by being themselves, I grew up in a world where I never really had to put myself at odds with the law because of my sexuality. As I grew up, I learned I could be myself and be a law-abiding citizen, too… for a while, at least.

My acceptance of myself as a gay man happened to coincide with a massive shift in how queer people were perceived in many countries around the world. By the end of 2015, it felt like marriage equality and minority rights were spreading across the world in a forceful wave of unstoppable progress.

photography by laura nguyen for queer history issue

But we all know how 2016 went. I was never delusional or naive, I knew there was a lot of work still to be done to make our societies more just and egalitarian. But it was shocking to see some of the vitriol that had been lurking beneath the glossy surface of my utopian fantasies. Though Canada was spared some of the worst, we don’t live in a bubble and what happens around the world has a big impact on us too. Watching what felt like the world burning, I was struck with a great sense of loss of control and bafflement at how quickly my hope could dissipate.

Was this finally my chance to protest, to put myself out there for a better world, just like Marsha P. Johnson and Harvey Milk and all the other queer activists that came before me? Not quite. Instead of activism, I turned to crime.

I hope you’re picturing me plotting getaways and whizzing across desert landscapes like the real baddest bitches of them all, Thelma and Louise. Keep that picture of me in your head a moment longer. Firmly ingrained? Good.

Unfortunately for my sexy criminal alter ego, this is not what happened. But for a few moments, I would feel like I had control again, like the violence of the world had subsided in the glow of my own personal chaos.

Nothing I did would have gotten me a single minute in prison, let alone a night. I wasn’t following in the footsteps of the queer activists who risked their lives for a better world. I was a dumb, selfish 20-year-old with a risqué hobby and no progress to show for it. I could keep acting out in petty ways, or I could try to live up to the legacies of LGBTQ+ activists that came before me, and actually try to make a lasting difference. Since my criminal fantasies, I’ve learned that talking is a much healthier way of working through emotions, and to take a stand against something you think is unjust you actually have to take a stand—one that might truly jeopardize your comfort and varied privileges. I’m not perfect, sometimes I act in selfish ways, lashing out superficially toward systemic discriminations against queer people. But I’m doing my best to not take my anger out in less productive ways.

It feels like, as a community, we’re facing an unprecedented and terrifying world right now, and collective action is one of the best ways to combat the rampant injustices we’re witnessing. That’s what the Stonewall rioters and HIV/AIDS activists understood. They weren’t protesting just for their personal gain—for a feeling of personal control—but for the benefit of everyone.

Now, when I think about my night in jail, I’m not alone. There’s a whole community of people there with me, all trying to make the world a bit better.

Kirsten Danae: Where were you in your creative career when you wrote this?

Jordan Johnston: I was in a transitional stage when I wrote this, having recently graduated from university and exploring what being a creative person meant outside of the structures and supports I was used to. The COVID-19 pandemic was also literally exploding around me also when I was writing the first draft in March of 2020, so the themes of control and injustice that I had planned to talk about were even more front of mind. I wouldn’t say that kind of uncertainty was great for me creatively, but being able to channel some of that anxiety into a positive direction through this piece was absolutely a balm at the time.

KD: What has your professional journey looked like since?

JJ: I’ve worked mostly in communications and engagement for public organizations since then, using my love of language and human connection to work on projects that are hopefully making people’s lives a bit better, or at the very least aren’t contributing to the unjust systems I was railing against in the piece. As the pandemic subsided, I was able to get back into performing improv around Vancouver again as well, which is a great creative balance to my professional life.

photography by kirsten danae

KD: One piece of advice for young people in the queer/creative community in Vancouver?

JJ: There’s a lot of pressure in our society to monetize our passions, and as creatives to feel like we’re failures if we’re not making a living off our output. It took me a while to learn that working a normie job to make ends meet doesn’t negate who I am as a creative person, and that my journey through my writing and art is lifelong without a specific time limit for “success.” Even when times seem tough, life should be enjoyed, so do whatever you need to that helps you live the fullest life possible, even if that means a 9 to 5. (Caveat: I know the job market sucks right now but I remain optimistic that the boomers will one day retire and that AI won’t take all our jobs—maybe I’m delusional!) And young queer people, at the risk of sounding 300 years old—get outside, meet people, go to queer bars, join gay clubs, whatever helps you find your people. Queer family is important!

KD: In your piece, you talk about petty crime. How did you finally satiate that craving? And what have you discovered about yourself in its absence?

Fortunately, my desire for petty crime was a pretty brief sojourn that has long passed. I was responding to a loss of control, which to be frank has only been amplified in the years since this piece was published. I still think that the best antidote to this feeling of helplessness is collective and direct action, but I can’t say that I’ve found my perfect outlet yet. I’ve found a lot of solace in community since the pandemic, and I’m excited to see where my next steps take me. All in all, it’s still a work in progress without a clear answer, but come talk to me in another 5 years!

Jordan Johnston is a communications and engagement coordinator for public organizations based out of Vancouver. In his free time, he dabbles in improv, and you may catch him on a stage somewhere in the city when he isn’t working hard at his day job. You can find him on instagram @jordansjohnston .