SAD Again: Why We Deserve Safe Spaces

/From the moment I moved to Vancouver, I was told it was easily the most inclusive, multicultural city in Canada. And when that’s your lived experience, it’s easy to believe. Many can afford to look past the racist remarks and misogynistic comments, particularly when these can be classified as microaggressions, but that should never expunge the effect they have on others.

In reading Sunny Chen’s piece “Why We Deserve Safe Spaces”, published in SAD’s 24th issue in 2017, I thought of how much—and at once how little—has changed since then in a country that preaches progress but can’t help but overlook the wrinkles on its otherwise smooth facade. Sunny, who often goes by their artist name Sunny Daydream, opened up about their experiences living in Vancouver, the changes they have perceived since writing the piece and the trajectory of their professional journey as a creative.

sunny daydream chen photographed by ashley sandhu-kim of array photography

Born in Nanjing, China, Sunny was raised in Langley and has since graduated with a BA in Psychology and a minor in English Literature, going on to publish their work in magazines like Bloom, Contrast Collective and the Garden Statuary. Singing and performing since the age of 3, they have since come out with their own original singles as well as a dramedy pilot “Open Ethnicity”, which truly speaks to the range of their talent. Though I am newly acquainted with Sunny’s work, I was at once struck by the sharpness of her writing, radiating authenticity and inviting challenging conversation with plain boldness and candor.

Why We Deserve Safe Spaces

Words by Sunny Chen

Photography by Joy Gyamfi

“You’re barely a woman of colour.”

That’s what my white coworkers told me one day during a smoke break. I had just expressed that I wasn’t feeling well, and wanted to talk about my recent experience of racism and misogyny. Unable to hide my shock to their response, I blurted out, “No, I am—I’m an immigrant,” and then resigned to smoking in quiet, too tired to open that can of worms.

Don’t get me wrong; my coworkers are wonderful, intelligent women who have carved out their own spaces in the industry they work in and the social circles they exist in. But to minimize the trauma I’ve experienced by telling me that my skin is merely two shades darker than theirs doesn’t revert the ongoing effects of racism and white supremacy.

If I am not perceived as a woman of colour, why did that man single me out on public transit to accuse Asian men of having small penises? Why did he ask me, “Is that big for you?” As I ate my Cheestring? Why did he ask me, again and again, from three seats away, “Is that big?” with a jeer frozen on his grimy face, suggesting that my cheese snack was a penis, and it was too big for me? Even after I confronted him about his crude joke, he went on a tirade about how there are too many “chinks” in the city now, and that they all have small penises. He continued to spout fallacious racial stereotypes, changing his focus to the Indigenous population. “All of you should be killed off,” was his conclusion. The tirade went on like this until he stepped off the bus. He smiled at me as he exited.

These minor instances of overt racism remind me that non-men of colour are very vulnerable in our society. Every individual exists under multiple layers of vulnerability, stemming from ethnicity, income, gender, sexual orientation, and other forms of hierarchy. And every individual with a unique mixture of vulnerabilities deserves to feel safe in all spaces. As an artist, my work comes from my ongoing experiences of racism and misogyny, and is obstructed by both. Ethnic minorities and non-white people are still being targeted for discrimination in this country that I call home. Even during high school, there was a distinct racial segregation between white and Asian students. I grew up thinking that girls of colour were inherently uglier and less popular than white girls, because white students never asked us to see movies or invited us to parties. The most demeaning experience in high school for me was when a white girl one year older sat on the stairs and hurled pieces of food at me, yelling racist slurs.

As a first-generation immigrant, I choose to claim both Canadian and Chinese cultures as my own, even though everyone seems to have their own opinions about how Canadian or how Chinese I really am. Second-generation Canadians or people of mixed ethnic descent may find it much more difficult to claim a culture as their own, or find affinity and acceptance from any one cultural group. Chinese-Canadian author Fred Wah expresses the idea of “living on the hyphen,” which describes what life is like for individuals of ethnic minorities. Like many other people of colour, I may never fully connect with a pre-existing cultural identity—we must create our own, through trial and error.

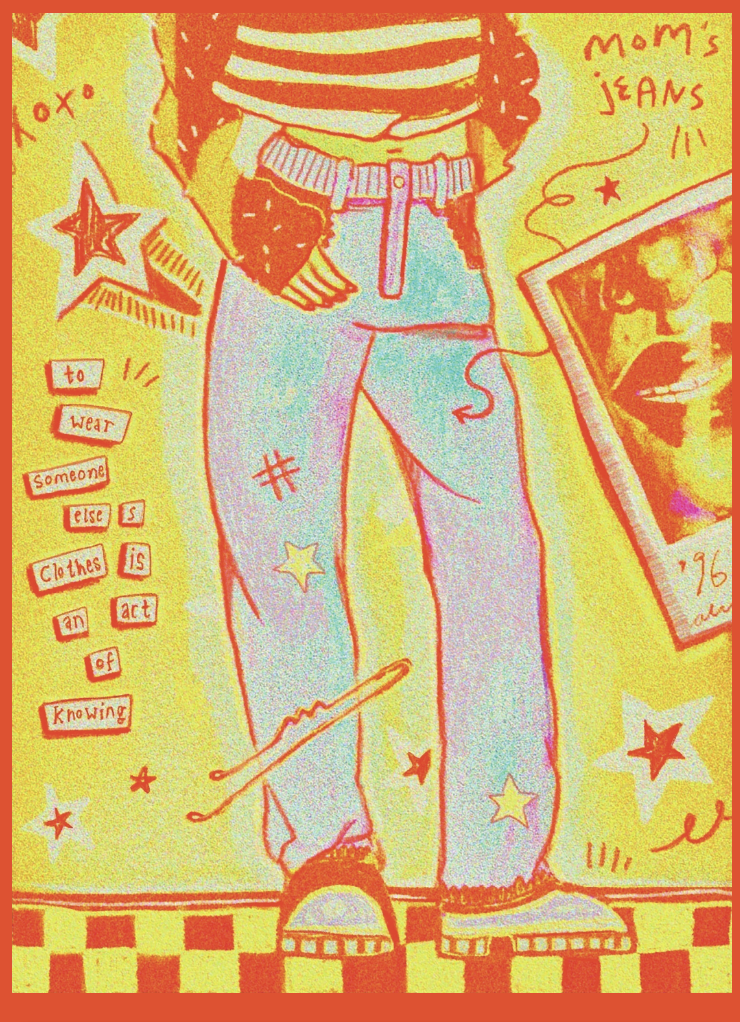

photo by joy gyamfi for issue 24: Space

Sometimes I wonder how many other young femmes of colour have experienced the racial microagressions that I have encountered. Have you waited at the bar of a busy club while white bartenders served multiple groups of white people behind you before acknowledging you? Have you showed off your dance skills at a party and overheard a group of boys say loudly, “I didn’t think she’d be the one doing that”? Then at the same party, when you’re digging through your tote bag on the floor, have you had a girl ask you if you’re “doing the Asian squat”? And when you say, “No, I’m looking for something in my purse,” she proceeds with, “Only Asians can squat like that, though, because you have flat feet,” as if she is stating a fact? And this girl is not a white girl, but a woman of colour, too, although she’s not East Asian. Who do you talk to about these small yet complex instances of stereotyping, without feeling like a burden?

I have learned that I need safe spaces to speak openly about my experiences as an immigrant woman of colour. In the film/TV and music industries I work in, white men dominate the spaces, which results in frequent racial and misogynist microaggressions that I immediately push aside in order to function on a day-to-day basis. This repression of trauma has, at times, affected my ability to communicate my emotions in healthy ways with my partner, friends, colleagues, and even strangers who are within my vicinity. Everyone has different privileges: I have the privilege of presenting as mostly heteronormative in a heteronormative society, being physically abled, being a socially acceptable body size, and speaking fluent English. I don’t have white or male privilege. I also don’t have the privilege of discussing racism and misogyny with my family—a common thread among people of diaspora.

I have never relied on my family for emotional support, even as a child, because I am not able to. I do not have the Chinese vocabulary to express my experiences to them, nor do I have the emotional strength to speak about trauma with my mom. How would she understand my “western” lifestyle? In my mother’s eyes, the world is a dangerous place. She has always instructed me to never step foot outside after 10 p.m., and if I must, I should bring my boyfriend along (whether I have one or not). In her mind, I must protect my body by leaving it at home, or in the hands of a male guardian. Her logic dictates that I stay inside when the sun sets, to avoid being raped and murdered.

Where can I learn to protect not only my body, but also my mind, from the trauma I experience? I am getting tired of surrendering my right to personal space on public transit. Thankfully, as an adult, I have found safe spaces to learn self-care and receive protection. They are varied, ranging from conversations with close friends, to by-donation dance and wellness classes, to free counseling sessions at the youth clinic. A female counsellor taught me that I do not need to fight misogynists or racists every time I encounter them. I know now that I need to choose when I expend emotional and physical energy to combat misogyny and racism, and when I rest my mind and body. We all deserve to rest, and we all deserve safe spaces. Without them, I would not be able to process my experiences, or write them down.

The creation of safe spaces should not be the sole responsibility of vulnerable populations that are most affected. We need the help of venue owners, club promoters, teachers, business owners, students, writers, editors, musicians, photographers, commuters on public transit, and everybody else to tune into the importance of safe spaces and normalize them for everyone. We need spaces to process our unique and shared trauma, to give and receive advice, to release warnings about abusers in our communities, and to express pain without shame because it’s okay to be vulnerable. On a smaller scale, a safe space can be friendships in which you can discuss your lived experiences with each other without being denied, harassed, or pressured, either online or in the physical world. Try posting about a recent microagression on social media. Unfollow or block anyone who doesn’t support your right to speak up. Schedule hangouts with the ones who do, and perpetuate the existence of safe spaces with them.

photo by joy gyamfi for issue 24: Space

Kirsten Danae: Your piece touches on sensitive topics of racism and social conditioning that can be easily overlooked in a city like Vancouver, often praised for its liberal policies and culture. What kind of changes have you noticed in the past eight years since your piece was published, if any? What kind of changes would you like to see in the coming years?

Sunny Chen: Since the COVID outbreak in early 2020, I've noticed how everyone averts their gaze when walking down the street. Unless you're perceived as wealthy, people will ignore you or treat you like scum. I've also noticed more instances of overt anti-Asian and anti-Indigenous racism. There's a lot of anti-Asian and anti-Black history specifically related to Vancouver that has never been addressed; I hope more people will research Vancouver's history. During the lockdowns, I participated in blockades supporting Wet'suwet'en and Hogan's Alley, which shut down entire streets, port terminals, and the Georgia Viaduct for several days at a time for months, and resulted in many arrests and long-term trauma via the policing industry. These protests haven't been given the same respect or resources as other national news. I lived in Strathcona from 2019-2021, and moved back in with my mom and grandparents in Langley for 5 months before finding housing. The homeless encampment was pushed to Strathcona Park for almost a year in the beginning of the pandemic, and the City did nothing to help unhoused people. Mutual aid and social media kept folks alive. Vancouver is a classist and conservative city. I'd like to see the dismantling of classism in the coming years. For example, landlords shouldn't exist. Everyone deserves to own their own home, take care of their own home, and have stable housing as a human right. There needs to be more affordable housing and social housing, not for-profit investment properties. Spotify CEO invests in AI military weaponry and Apple exploits child labour in the Congo just to hoard more money... while there are unhoused people? Corporations are literally evil. Also, in no way should we normalize "wildfire season". We can prevent climate destruction - we can hold corporations responsible by putting our money elsewhere, especially towards local businesses and secondhand. It's easy to switch to Tidal or Qobuz for music streaming and buy secondhand tech from Reebelo.

KD: What advice would you give to emerging creatives that may be struggling to make themselves heard in a predominantly white/heteronormative industry?

SC: Listen to your intuition and show your authentic self. In order to stand out, you have to get your work in front of people who are like you, and collaborate with people who understand you. The rest of the industry doesn't matter in the long run. With TikTok and YouTube, traditional gatekeepers are obsolete. You have the power to find your audience and make art for your audience.

KD: You have dabbled in a few different fields as a creative, from writing in magazines like SAD and the Ubyssey to performing and even directing film productions. What has your professional journey looked like since publishing this piece?

SC: Since this piece was published in 2017, I've written and directed a web series pilot Open Ethnicity about the highs and lows of Hollywood North a.k.a. Vancouver, organized two series of free community workshops partnered with the Vancouver Public Library and Decipher Counselling and played Music Waste Festival twice. I have also played in other festivals like Vancouver Outsider Arts Festival, Jade Music Festival and Surrey Fusion Festival as Sunny Daydream. I have released a studio album with the support of Creative BC and SOCAN Foundation as Sad China, wrote my original play about 20th century China based on my familial history (my grandma was sent to a labour camp as a kid because her dad was a teacher), started seeing a queer 2nd generation Chinese Canadian registered counsellor and created art and organized events to hold space for SA/DV survivors. I've realized my work revolves around collective healing because I don't see that much in a city like Vancouver, where everything gets swept under the rug and people are too polite to be real or repair from conflict. I've also acted in Lifetime movies, network shows, and national commercials, although I joined the union in 2023. I worked on Peabody award-winning game 1000xRESIST as a voice actor. I'm on a hiatus from film/TV but this time away has really helped me and I'm pumped to get back into it in the next couple of years. My one true love will always be writing though, whether that's music and lyrics or screenplays, grant applications and Instagram captions.

KD: Finally, I have to ask, what’s next for Sunny Daydream?

SC: Before 2025 ends I will be releasing a lyric video for “2 Lonely” with Yaris Paris and making more synthpop music as Sunny Daydream— looking to release a music video in 2026. Hopefully you will also hear my voice in upcoming animated shows and games! I also plan to take time to heal my trauma, help my community heal from theirs, share my true self on the internet and cuddle my cats. You can find me on TikTok: sunny__daydream, Instagram: @sunnysxc, and at sunnydaydream.net.

Kirsten Danae (she/her) is a writer with a passion for film and the occasional excess in caffeine. She grew up in Mexico before moving to Vancouver to study English and Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia, and in her free time enjoys watching and reviewing movies so she can write one herself someday. Follow her on IG @keeks_diner