"K.O.T.B." by Cedar Jones

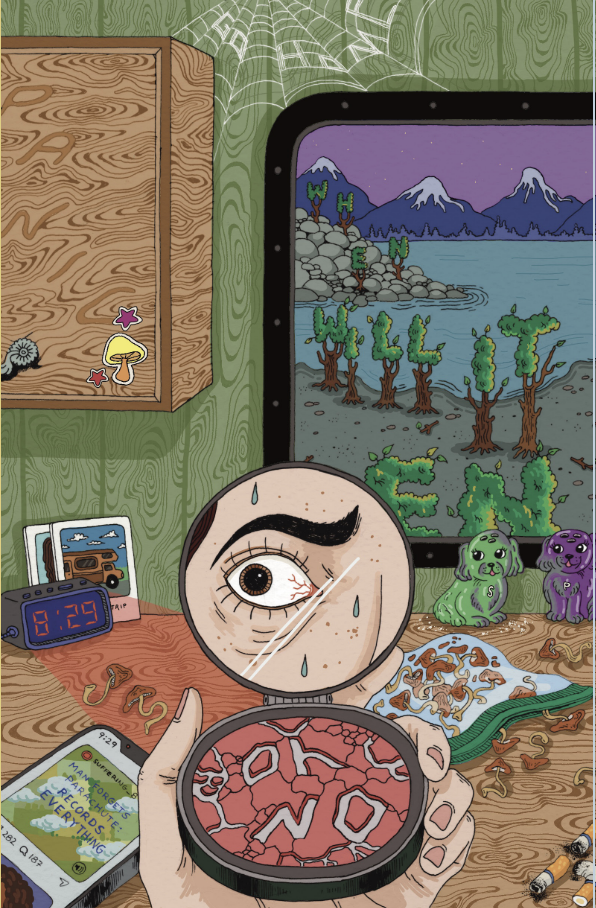

/collage by nicole johnson: “Woven into the geographical area of the downtown East Side are the four colours from the medicine wheel. These colours represent physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well being. I wanted the shared respect to tie into the piece while having those who occupy the space in mind.”

We were down on East Hastings, where people, shelters, and garbage were tucked into corners and scattered across sidewalks. There were a few of us handing out hot soup and supplies when I heard someone call out up ahead.

"Kid on the block! Kid on the block!"

The call echoed from one person to another down the blocks behind us. It triggered movement, particularly in places where there hadn't been any. Some people tucked what was in their hands out of sight and rearranged their belongings. Some people turned around to face away from the street. Every person knew what that call meant, and parted down the middle to give a wide berth to a parent pushing a stroller down the sidewalk.

I was visiting Vancouver to take some time for myself. I wanted to eat some babka from Kozak, sip espresso, and work on some poetry. The purpose of my trip changed when I saw video footage of the encampments in the Downtown Eastside being dismantled by the police. How could I comfortably indulge myself in Gastown, knowing that people were being removed from their shelters–their homes–and left out in the rain only a few blocks away? I came to Vancouver to relax and be alone, and instead, found myself witnessing a level of care on the block that made me grateful for my change of plans.

"Kid on the block" showed awareness.

"Kid on the block" showed respect.

"Kid on the block" showed consideration exercised by a community that rarely receives the same. I watched a woman drive by slowly, just moments before I heard the call down the block. Her eyes fixed on us as she mouthed, “Pathetic.” These people are mistreated and misunderstood, and still, they made room for a parent and their kid.

Imagine if smokers outside a pub instinctively moved their whole group to avoid exposing a child to secondhand smoke. That doesn’t happen because their survival isn’t dependent on it. Because smokers and drinkers aren't at risk of being removed from their homes for their public behaviour. They aren't at risk of having their possessions taken away if their smoke wafts as a stroller rolls by. Exposure to secondhand smoke is a health risk that affects more than just the smoker; most other things found on the block do not pose the same risk by mere proximity. My point here is not to compare smoking and drinking to other substance use. I don't believe there is an "elite" poison. All poison is poison. Whether it is legal, regulated, or not. My point is to draw attention to the incongruity surrounding the subject.

"Kid on the block" shows a level of humanity that has been dug out from deep fear and deep shame. These four words can move a whole community. They were learned—and are taught to each new arrival on the block—with a purpose. A purpose that caters to community care, which is more purpose than most people carry with them as they hurry through these streets, gaze averted.

"Kid on the block" means, "Hurry, get out of the way. Hide your vices. Cover yourselves. Make room. Make lots of room, because there is a mother with a child walking down the street, and we don't want to make her feel uncomfortable."

"Kid on the block" means, "We know it is troubling for you to see us, to see our addiction, to see our pain, to see our struggle, and we don't want to expose you or your child to that."

“Kid on the block” is the voice of a caring community. This care is not reserved for those who are visiting or passing through. This care is a manifestation of love, and it permeates the community. This love comes in the form of Naloxone kits hung from fences and street signs. This love is a lap for a head to rest on, rather than having to lay on the concrete. This love is drug testing and safe injection sites to keep each other safe. When a life is lost, this love blooms beautifully, albeit painfully, in the form of memorial art and brings the block together to hold each other in grief.

Imagine what life could look like if everyone protected each other the way that this community tries to protect themselves, that woman, and her child. Imagine what the block could look like if others showed them the same care. I wish people could exist without feeling like they need to sweep themselves into corners for the comfort of others. What are we teaching them? What is that teaching us? What could they teach us if we listened?

We are told, "The removal of these encampments is a response to public safety concerns." I think the real threat to the safety of the public is that we don't know how to treat each other with the urgent respect I witnessed on those blocks, as those who had nothing left to lose still lifted their voices and cleared a safe path for someone who couldn't even make eye contact with them.

The real threat is that we are losing our ability to see.

Cedar is a Sioux musician, writer and spoken word performer who has taken a fast rise in the artistic community of southern Vancouver Island. The shape of her creativity was carved out by the ocean, the trees and a western breeze. She honours her fathers spirit by pulling inspiration from the earth for much of her work, and uses the sharp teeth her mother gifted her to give her delivery some bite. Her writing and musical compositions tell stories that reflect her raw vulnerability and appreciation for life. Find them on Instagram at @shesjonesy.

Ha7lh skwayel, my name is Nicole Johnston and I am an indigenous artist from the Squamish nation, situated in Vancouver. Much of my work incorporates traditional Squamish mediums and cultural values. While my work has a primary focus in painting, I am actively exploring textiles, photography and sound to convey my perspective and appreciation for the natural world around me.

We encourage readers to learn more about and support DTES-based initiatives, such as Insite—North America’s first supervised drug injection site—and mutual aid networks, such as OUR DTES and distro disco, that have been keeping our local communities safe.

- SAD Mag