xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł: Manuel Axel Strain’s multimedia exhibit remembers teachings from ancestors and the land

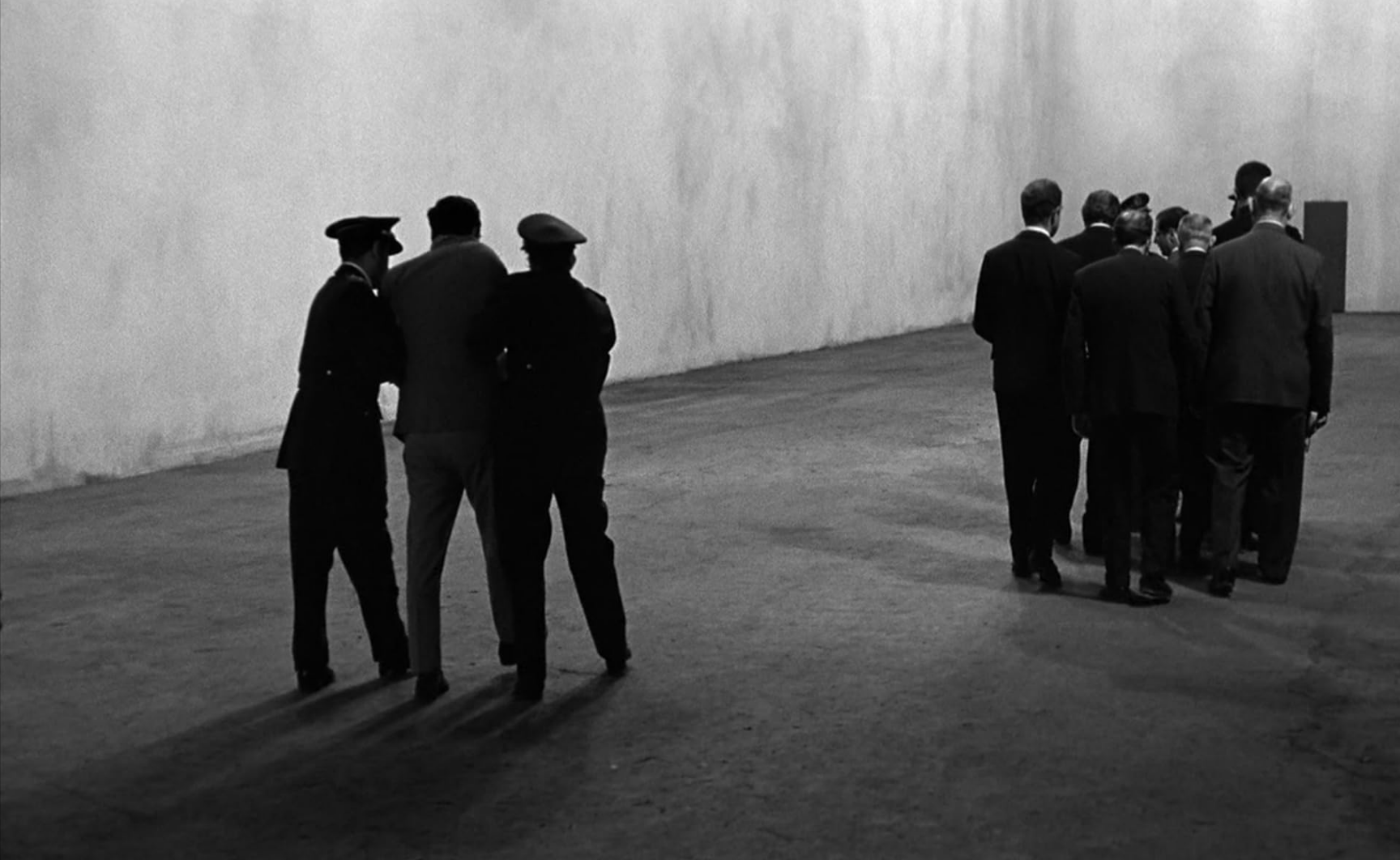

/Installation view of Manuel Axel Strain, xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł ((((Remember your teachings)))), Richmond Art Gallery, 2025. Photo BY Michael Love Photography. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE RICHMOND ART GALLERY.

The soft aroma of Devil’s Club drifted through the air. A mixture of Indigenous flowers, juniper, sage and cedar dusted the ground, remnants from the opening of Manuel Axel Strain’s solo exhibition at the Richmond Art Gallery (RAG), titled xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł ((((Remember your teachings)))), which opened on September 13 and runs until November 9, 2025.

Around the gallery hang large photographs of natural and urban settings interwoven with clouds, trees, and waters, punctuated by pictograms in bold, vibrant colours. At the centre of the gallery stands the exhibition’s focal point: a physical re-interpretation of a traditional longhouse.

Strain painted the exterior in sunset colours to symbolize transformation, a concept central to Musqueam teachings. The edges of the longhouse are lined with Coastal Interior Salish red ochre, nesting a pattern of black and white, representing what Strain describes as “dialectical thinking.”

Strain’s vivid imagery and abstract forms grab attention and spark wonder, yet beneath each work lies a deeper inquiry: an exploration of nature, science, technology, and humanity’s interconnected, often tense, relationships. Chemical compounds can heal or be toxic; fires can warm a longhouse or devastate landscapes; AI can isolate and dominate or foster creativity and generative recentering of Indigenous ways of thinking. This duality present through the show echoes the dialectical thinking encoded in the black-and-white patterns of Strain’s longhouse.

Manuel Axel Strain, xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł ((((Remember your teachings)))), 2025, Longhouse (wood, paint), mural, oil on canvas. Photo BY Michael Love Photography. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE RICHMOND ART GALLERY.

Stepping inside, visitors are enveloped by the fragrance of cedar. On the ground, in place of a traditional fire, a projection flickers, depicting an Indigenous family playing in the snow and embracing near water as industry looms in the background. The scene captures both tenderness and tension, a meditation on the persistence of family bonds and the resilience of Indigenous culture, revitalized and celebrated amid centuries of colonial pressures.

The title of the exhibit, xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł, is in the downriver dialect of hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ (Halkomelem). Strain is a Two-Spirit visual artist and cultural worker from the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Simpcw, and Syilx peoples. Their work is a personal journey into family and ancestry, grounded in Indigenous epistemologies challenging colonial structures while bridging traditional and contemporary knowledge systems.

Strain’s RAG exhibition was initially meant to build upon a previous exhibition of their work, xʷəlməxʷ child, with pieces first shown at the Polygon Gallery earlier this spring. However, the curator notes that, being the prolific and ambitious artist they are, Strain created entirely new works for this exhibition, including a large mural specific to RAG depicting a simple human-like pictogram flying over a photograph of a shoreline stretching an entire wall.

As a multidisciplinary artist, Strain’s work fully engages the senses. On September 27, Strain hosted a sensory talkback with their friend and artist SF Ho. Together, they explored Strain’s exhibition through smells, sharing traditional herbs and plants from Strain’s Indigenous lineages taught by their mother, alongside Ho’s memories of their grandfather’s Chinese apothecary and study of scents.

One by one, the audience smelled juniper, cedar, sage, ginseng, ai cao, and other Indigenous and Chinese herbs, fresh, dried, boiled, and extracted into essences.

Detail view of Wildflowers (from witnessing ceremony at opening reception), Manuel Axel Strain, xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł ((((Remember your teachings)))), Richmond Art Gallery, 2025. Photo BY Michael Love Photography. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE RICHMOND ART GALLERY.

“If [sage] comes as a gift, graciously accept, but I would encourage everyone to not harvest these plants,” Strain warned, noting that simply touching them and smelling them where they grow is already healing. When asked why sage is overharvested, Strain answered without hesitation: “Cultural appropriation.”

Devil’s Club, a plant found in Coast Salish lands, is a medicine in the spring and summer, where even the steam is beneficial. Strain explained that harvesting it in the winter renders it toxic. An audience member hypothesized that the toxicity might be because sugars move into the roots during winter to conserve energy.

Science didn’t end the conversation, but expanded it, mirroring Strain’s creative investigation of the interface between science and plants as medicine. They thread together scientific observation with cultural knowledge passed down through family, elders, and embodied knowledge keepers, whose faces peer out in much of Strain’s work.

In one larger piece, Strain examined active compounds in certain Indigenous plants, including paclitaxel, derived from the Pacific yew tree and used in chemotherapy. They asked AI to create imagery magnifying the compound, then created an abstract reimagination of the compound against a bold purple inspired by the now mostly extinct Musqueam flower.

“It feels like your practice is asking us to build on natural intelligence, community intelligence, and relational intelligence,” an audience member at the talkback asked. “AI is the antithesis of that, so why did you choose to use it?”

Strain responded: “I’m researching ethical ways in which we can engage with it that are complementary to ways of Indigenous intelligence or relational intelligence. Because the alternative is that Indigenous voices are left out of that discussion, and that is more harmful.”

Strain’s multilayered work does not feel like a gimmick or indulgence in technological novelty, but an intentional exploration of how AI and contemporary science can be used creatively in relation to nature and Indigenous ways of healing.

They draw on the analogy that AI is like forest fires: a reality that will not go away, but Indigenous people have used controlled burns to mitigate them. “We have Indigenous intelligence coming up at the same time. Instead of creating opposition towards each other, they have to create a synthesis.”

This idea is reflected in a series of small paintings surrounding the longhouse, each just a few inches wide, depicting pictograms of drug compounds rendered in bright turquoise negative space over images of raging forest fires. The works offer a pointed commentary on the climate crisis and the drug crisis against the backdrop of an uncertain AI-charged future.

Manuel Axel Strain, Transformation Song, 2025, Pastel Drawing. Photo BY Michael Love Photography. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE RICHMOND ART GALLERY.

Towards the end of the talkback, Ho passes around fragrances evoking rain on stone and wet clay, and remarks that Strain changed the way they look at rocks and stones. Strain adds, “Rocks are also our relatives, in addition to plants. Think of volcanoes or going deep into the earth. It’s all moving. It’s all a lifeform in itself.”

The show reminds us that rocks, plants, and the natural world are alive and kin, inviting viewers to reconsider their relationship with them. Strain’s work continues to ask: How do you remember your teachings with the land in a capitalistic, colonial, extractive reality?

“I’m getting humans to form better relations with the land,” Strain observed. “If there’s a way for [nature] to communicate with each other, there must be a better way for us to communicate with them.”

Later on, a child visiting the gallery pointed to one of the red face-like illustrations on the side of the longhouse and asked Strain, “What does this mean?” Strain answered that they brought the faces out from the knots in the wood of the longhouse.

“Here’s another one,” the child exclaimed, revealing how Strain’s work continues to invite new ways of seeing, where nature is humanized, and humanity is re-rooted.

Manuel Axel Strain’s exhibit xʷən̓iwən ce:p kʷθəθ nəw̓eyəł ((((Remember your teachings)))) is on at the Richmond Art Gallery from Sept. 13 to Nov. 9, 2025, and open every day except statutory holidays. There will be an in-person art talkback and interactive art-making session with Strain and Musquem artist Zoe Kompst on Oct. 14, 2025, and an Artist Salon Webinar on Oct. 22, 2025.

Melody Yun Ya Ma 馬勻雅 (she/her) is a second-generation Hakka Toisan Chinese writer and cultural organizer based in Vancouver on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. She leads the SaveChinatownYVR campaign and is a founding member of Kirin Rising 麒麟革命, the only active queer, women, and gender-diverse-led Hakka kirin Chinese unicorn dance troupe in the Americas. Melody’s writing and advocacy on cultural equity and racial justice have appeared in outlets including The Economist, CBC, Maclean’s, and the Globe and Mail. She is a fellow of the EU’s Global Cultural Relations Platform and the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC). You can follow her work on Instagram at @melodyyyma and on X at @melodyma.